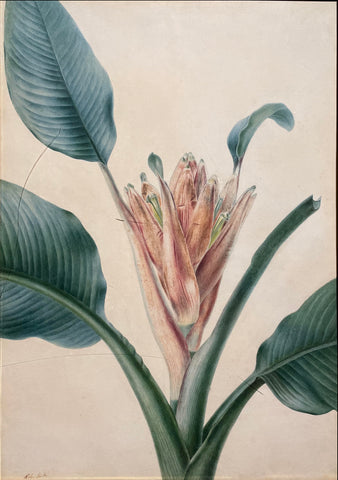

Pierre-Joseph Redouté (Belgian, 1759-1840), “Rosa Geminata” (Gemini Rose)

Prepared for Les Roses (1817-1824)

Watercolor over traces of black chalk on vellum

Signed in pen and brown ink, lower left: P. J Redouté

Sight size: 14 ¾ x 10 in.

Frame size: 21 x 16 in.

“In Germany, the rosy-flowered rose grows with the R. pumila. Professor Rau, who was kind enough to send it to us, found it on the Schwabenberg, near Rirtzingen, five leagues from Wursbour. We see it again, near the latter town, in the argillaceous parts of Mount Hexenbruch: its flower can pass, among the simple ones, for one of the most beautiful of the kind. It seems that the

It appears that the tube of the calyx is liable to vary, and is sometimes found to be covered with glandular hairs. We have previously placed it in the series of white roses, the shape of the tubes and the fruit, and the leaflets almost round, above, hairy beneath and simply dentees, characteristic of R. alba. But we must say that Mr. Rau, in his correspondence, disputes this conclusion, and considered R. Geminata as a distinct species.”

Exceptional Watercolors Painted for Les Roses

These exceptional watercolors are notable examples of Redouté’s achievements as a botanical painter relating to one of his most celebrated projects, Les Roses.

The rose-mania in France in the early years of the nineteenth century is far less known than the tulip-mania of the seventeenth century. The French aristocratic association with this flower began with Madame de Pompadour, and after the revolution, the Napoleonic dynasty and subsequent royal families devoted themselves to the rose. As a result, rose gardens and rose decorative motifs became very popular, appearing on furniture and porcelain, woven into fabrics, women wore roses in their hair or garlands of roses in their hands; roses seemed everywhere.

Empress Josephine acted as a catalyst for the development and introduction of new roses at her estate Malmaison. Josephine introduced roses into the garden collection in 1804, many of which were wild varieties. Empress did not arrange her roses formally but instead grew them in pots in glasshouses or spread in loose collections throughout the garden. This manner reflected a nineteenth-century trend away from formal gardens toward a more English style of gardening.

Although Joséphine died three years before the publication of Les Roses, it was the unparalleled collection of roses on her estate at Malmaison that provided the artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté with inspiration. The watercolor paintings and stipple-engraved plates prepared for Les Roses have been the most recognized aspect of the series, but the text remains valuable as well. The text accompanying each image was written by Claude Antoine Thory (French, 1759-1827). Thory was an ardent botanist who shared with Redouté a great love of roses; the two had neighboring estates around 1814. One of the aims of Les Roses was to highlight unique cultivars of roses. Other botanists are mentioned in Thory’s text but often as a way to disparage their research or surpass their variety. This was a two-prong effort in that both botanists and artists could set Les Roses apart as outdoing competing publications while also bolstering the importance of the gardens from which each specimen was procured. Specimen roses were procured from the gardens at Malmaison, collections of Thory, and other collections around Paris. The scientific details provided by Thory remain of great importance to art historians and botanists alike.

Born into a family of artists in the Belgian Ardennes, Redouté’s talents were recognized and encouraged from an early age. His Flemish origins were significant to his development as a botanical painter, for it was in the Netherlands that the genre truly flourished. The eventual recognition of still life painting in France was primarily due to the arrival of Dutch artists, such as Gerard van Spaendonck and Redouté, who popularized the field.

In 1782, Redouté arrived in Paris his entrée eased by his brother, Antoine-Ferdinand, who had already established himself in the city and had achieved some success as a decorative painter. Redouté was quickly attracted to the greenhouses of the Royal Jardin des Plantes, and it was during a drawing expedition to the Jardin that he enjoyed a chance meeting with the noted amateur botanist and collector of rare plants, L’Héritier de Broutelle. L’Héritier taught Redouté about the dissection of flowers and their scientific representation and commissioned him to participate in the illustration of his Stirpes novae. This directive was a crucial turning point in Redouté’s career, increasing the young artist’s interest in the science of floral painting and leading to his involvement as a founding member of the Linnean Society of Paris. His institutional affiliation brought him the position of the painter to the Cabinet of Marie-Antoinette, allowing him access to the Trianon gardens and providing an introduction to Gerard van Spaendonck, Flower Painter to the King. This master was to teach Redouté the technique of painting on vellum, and around 1785, he produced several works for the famous Vélins du Roi under Spaendonck’s direction. By his own account, his student’s work was more delicate than his own.

Redouté had, as pupils or patrons, five queens and empresses of France, from Marie-Antoinette to Joséphine’s successor, the Empress Marie-Louise. His devotion to botanical illustration was secured during the French Revolution when the competition of 1793 determined that he would continue the botanical illustrations for the Vélins, thus succeeding Spaendonck. Despite many changes of regime in this turbulent epoch, he worked without interruption, eventually contributing to over fifty books on natural history and archeology. However, his masterpieces were those completed at Malmaison for the Empress Joséphine.

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend