Search By Artist

Benjamin Wilkes (died 1749)

English Moths and Butterflies

London, 1749 (first edition, 1773 (second edition, 1824 (third edition)

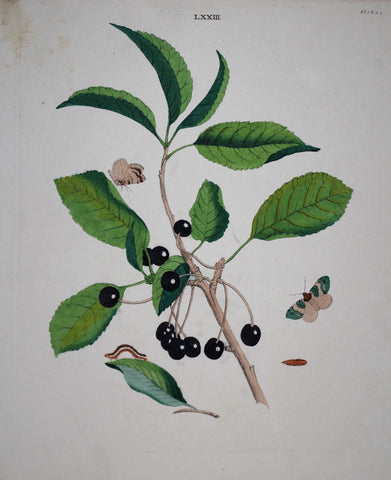

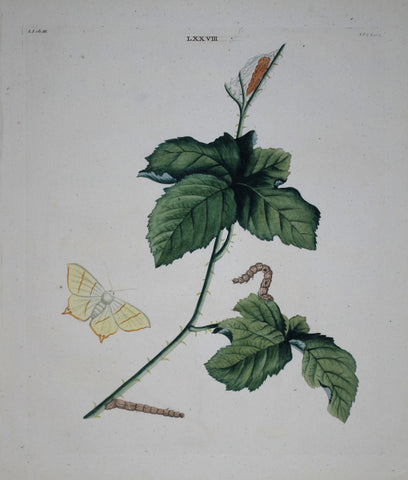

Engravings with original hand-coloring.

Little is known about Benjamin Wilkes, the author of The English Moths and Butterflies. In the preface to the work, he tells us that 'painting of History Pieces and Portraits in Oyl' was his profession, but that he often felt at a loss to understand what colours would contrast and set each other off to best advantage. Then a friend invited him to a meeting of the Aurelian Society, dedicated to the study of insects. Here, he first saw specimens of butterflies and moths which in their disposition, arrangement and contrasting colours struck him 'with amazement' and convinced him that nature would be his 'best instructor'. Over the next ten years he spent his leisure time collecting, studying and drawing caterpillars, chrysalids and flies, greatly assisted by the well known naturalist Mr Joseph Dandridge to whose collection he had free access. This publication was the culmination of this work, a perfect combination of artistic skill and specialist scientific observation.

The English Moths and Butterflies was a large and ambitious work. Its colour plates portray the complete life cycles of individual species on their host plants, while the accompanying descriptions contain details of their ecology, morphology and habitat. Although this first edition was undated, it was probably produced in 1749. Dedicated to the president, Council and fellows of the Royal Society in London, it was popular enough to warrant a further two editions. The second edition - basically a reprint of the first, with a different title-page - appeared in 1773; although the original blocks were again used for the illustrations of third edition of 1824, the type was completely reset and the text updated to incorporate the new system of Linnaean nomenclature.

While the main appeal of this work undoubtedly lies in its fine illustrations, Wilkes' depth of knowledge and enthusiasm for his subject also shines through in the accompanying text. His fascination with the 'company of insects' is evident in the preface where he expresses his sense of wonder: 'the Creatures here exhibited, are adorned with such a Variety of Beauty to engage our Notice, and undergo such amazing Changes in their Form and Appearance, that a thinking Mind can hardly avoid regarding them with uncommon Pleasure and a more than ordinary Attention'.

The detailed observations made about each species also underline Wilkes's great familiarity with and love of his subject. He tells us that the great yellow-underwing moth (shown at top), for instance, usually feeds at night as many other naked caterpillars do, to avoid being devoured by birds who are 'much fonder of the smooth caterpillars than of the hairy ones'. He frequently describes where and how he encountered each insect: for instance, he found plenty of examples of this same moth in 'the Gardens of John Philips, Esq at Layton in Essex; they were discovered, by the help of a candle and lanthorn, from twelve o'clock at night till two in the morning; and were so fearless, that they would suffer one to take them with the hand'. There is also much advice on how to keep any specimens caught. He cautions that the caterpillar of the Goat moth, for example, should not be kept in a box or anything wooden as they will eat through that substance, their natural habitat being the Willow tree.

Since the butterflies and moths in their various forms are depicted in situ with their host plants, the publication is effectively a flower book as well as a manual of lepidoptery. In the illustrations above, the small Ermine moth is shown with the Orange-peach with its blossom and the Swallowtail butterfly with the Meadow Saxifrage. It seems that Wilkes could occasionally be accused of exercising an element of artistic licence in this area, however, although he defends his position by claiming that the work would otherwise have been monotonous since 'the greatest part of the caterpillars described in this work feed chiefly on the Oak, Elm, Blackthorn, White-thorn, Willow and Nettle, all which are separately represented in different plates'.

The hobby of butterfly collecting has now fallen out of favour but was in its heyday in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. At this time, many species were found in abundance. Indeed, Wilkes writes of examples such as the Purple Emperor where 'I myself have seen twenty of them taken on the same branch one after another, for although the fly seems to be extremely wild whilst on the wing, yet, when settled, you may lay your net over it with little trouble'. In his advice on catching flies, meanwhile, he can jauntily declare that once your fly is captured you should 'stick it in your box, and look for more sport'. Sadly, two hundred and fifty years later, several of the insect varieties that Wilkes would have known have died out, while butterfly numbers are on the decline. It is therefore perhaps just as well that most people are now content to enjoy these creatures when they catch a glimpse of them in the wild. In Wilkes' defence, however, it must be pointed out that the present ecological situation is more due to loss of habitat than the work of over zealous eighteenth century gentlemen armed with nets and pin cushions. Wilkes came from a period that was a golden age for amateur interest in natural history; luckily for us, it was also a golden age for recording this enthusiasm in beautiful plate books such as this.