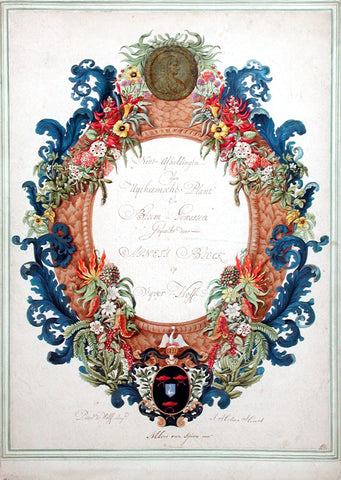

Herman Henstenburgh (Dutch, 1667-1726), An Urn Garlanded with Flowers on a Terrace with Shells in the Foreground

Herman Henstenburgh (Dutch, 1667-1726), attributed to

An Urn Garlanded with Flowers on a Terrace with Shells in the Foreground

Watercolor and bodycolor on vellum

ca. 1700

Paper size: 16 5/8 x 11 5/8 in

Frame size: 28 x 23 in

Serpentine, the garland placed around an urn grows outward, nearly penetrating the picture plane to offer a close-up study of the flowers and greenery of which it is made. Before a perfect, twilight sky with hazy hues of pink and purple, the objects of the middle- and foreground pulsate with vibrancy, luminous. Although tamed by being uprooted, clipped, and intertwined, Henstenburgh maintains nature’s wildness as the right side of the garland escapes the boundaries of his vellum paper. Exoticism exists in the array of seashells which signal the collection of objects by the artist and his ability to unite the foreign with the familiar. In the painting’s center is an urn, symbolic of mortality that complements the seemingly immortal state of the work’s wildlife.

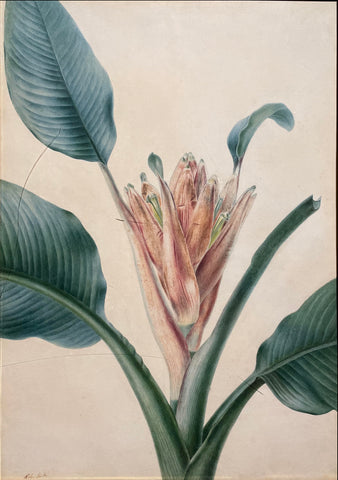

The development of natural history painting paralleled progress in the field of science. Drawing played an important role in the advancement of natural history and the influence of animal and plant illustration had a direct effect upon the development of allegorical and trompe l’œil painting.

The Dutch were at the forefront of these developments and managed to forge a remarkable synthesis between concern for scientific truth and the decorative and exotic aspects of natural history. Imaginative compositions joined flowers and birds with insects and reptiles to create fantastical juxtapositions imbued with allegorical meaning. Snakes, lizards, and frogs, had powerful symbolic connotations and were related to the theme of Medusa. Butterflies were also associated with mythology and specifically the story of Psyche and the theme of Vanities, in which the caterpillar corresponds to man, the chrysalis to death, and the butterfly to the soul after resurrection.

Herman Henstenburgh produced exemplary examples of this genre. In his remarkable paintings he breaks away from the somewhat limiting precepts of natural history painting to create a play of lines and colors that can be appreciated not simply for its decorative aspects, but also as a departure from the naturalist’s strictly narrative view towards an art approaching abstraction. Henstenburgh was a pupil of Johannes Bronckhorst, a fellow native of Hoorn in the Netherlands and according to contemporary accounts, his early works very much imitated those of his master, depicting birds and landscapes. He later broadened his repertoire to include splendid flower and fruit pieces, and occasional woodland still-lifes. For his flawless draftsmanship and vibrant colors, Henstenburgh won considerable renown even during his own lifetime.

Likely supplemented by his career as a baker and chef, Henstenburgh’s works are often executed on vellum, an expensive choice of material. With low porosity which allows the paint to not be absorbed, the pigment’s vibrancy is retained as it sits on top of the paper. Henstenburgh himself brought forth this technique, leaving his mark on the growing intrigue in still-life watercolor during the late 17th and early 18th century. Too, these pigments are more pronounced through the artist’s use of thin, black or brown ink framing lines which provide a delicate, individualizing contrast between each plant, insect, and object depicted. With gentle, white highlights, Henstenburgh brilliantly executed his trompe l’oeil watercolors, referencing pre-existing modes of painting by refreshingly departing from them with his wistful yet detailed eye.

Henstenburgh initially educated himself through the copying of birds and landscapes by Pieter Holstein. Shortly afterward, as a peer of Johannes Bronkhorst, who, likewise, was a baker, Henstenburgh imitated Bronkhorst’s landscape and ornithological studies. The younger artist diverged from his master by focusing on botanical works, sometimes incorporating otherworldly landscapes in the backgrounds of his still-lifes. It should also be noted that his botanical watercolors are occasionally situated before a wall, implying a real space in which these fantastical bouquets and garlands exist. Though, Henstenburgh’s watercolors also have the tendency to omit colorful backgrounds, opting for greater contrast by retaining blank, white backgrounds that recall the insect and bird studies of the master from which he learned. In this way, the artist abstracted the presentation of his work, understanding that the lack of a concrete space further suggests removal from the temporal nature of a flower’s bloom.

Henstenburgh did not entirely diverge from Bronkhorst’s teachings. Indeed, crawling about Henstenburgh’s works are insects that bring further liveliness to his portrayal of nature. Additive, these insects--generally butterflies and snails--parallel the forms of flower petals and seashells. Then, a butterfly’s wing expresses the same fragility of a flower’s petal. The shapeliness of a snail’s shell mirrors that of seashells which are pictured in An Urn Garlanded with Flowers on a Terrace with Shells in the Foreground (ca. 1700) despite no other reference to the ocean. A means of expressing the collection of objects, like those in Wunderkammer, cabinets of curiosity which gained popularity in the 16th century and displayed manmade and natural objects collected as a result of global trade, the incorporation of seashells from an unseen body of water not only suggests the artist’s worldliness but, as well, reveals to the viewer his ability to acquire both the physical, collectible objects and the skill to duplicate them in his work. Often commissioned by Agnes Block, an artist herself and an early collector of natural history works and objects, his focus on detail, like the small holes chewed in leaves by seemingly harmless snails, was lauded for its basis in reality and expression of beauty found in nature.

Comparably, the presence of dewy water droplets on petals, leaves, and stone ledges attests to the artist’s skill--their translucent quality alludes to the feats of Henstenburgh’s predecessors, namely Pieter Claesz whose oil painting Still-Life with Wine Glass and Silver Bowl (mid-17th c.) continues to awe with its realistic depiction of glass. In a similar fashion, this inclusion of water droplets builds the artist’s skill-set, heightening his capabilities with his impressive attention to minute detail which may seem impossible to relay with merely a brush and paint. Not limited to flowers, Henstenburgh’s watercolors also give focus to fruit--namely, his painting of grapes possibly refers to the well-known tale of the ancient Greek painter Zeuxis.

In brief, the Greek artist competed against his contemporary, Parrhasius, to paint grapes--although Zeuxis’ naturalistic work fooled birds that attempted to eat the grapes, his competitor won the contest, misleading Zeuxis by claiming that his grapes were behind a curtain. As it turned out, the curtain was painted, tricking the other painter, Zeuxis, who conceded. While not exactly lifelike, beautified by the intensity of the pigment used, the attractiveness of Henstenburgh’s fruits, such as peaches, raspberries, and cherries, implies the artist’s interest in exemplifying the extent of nature’s perfection, rendering them as seemingly edible as Zeuxis’ grapes. In his day job as a baker, he specifically made pies, and, being closely acquainted with the fruit depicted in his watercolors, the artist’s familiarity with the subject matter gives reason to its successful execution. Still, further meaning can be derived from the motif of a bunch of grapes as it became representative of female chastity in Jacob Cats’ literary works of the 17th century which influenced later writers of the period. Further, another possible reading suggests that the vine, or tendril, of a grape is representative of the Virgin while the grapes themselves symbolize Christ. Considering these multiplicities of meaning, Henstenburgh’s works call out to viewers to become more involved with the work by drawing their own conclusions.

Although it cannot be determined that the artist made a living off of his watercolors, it is known that the English commended Henstenburgh’s work, adding his pieces to their portfolios of Dutch art. As he broadened his subject matter, creating scenes by adding backgrounds, man-made materials, and references to environmental realities such as dew, Henstenburgh’s watercolors individually display microcosms of his 18th century world. More than just a baker and a follower of his master, Johannes Bronkhorst, Henstenburgh expands upon an existing canon to more completely recognize the allure of his subject matter. Through employing playful linework and bringing in man-made objects alongside flora and fauna--like urns, busts, and vases--Henstenburgh’s watercolors introduced an acknowledgement of man’s inseparable ties to nature. By pairing his flowers, fruits, insects and animals with these objects, man and nature harmoniously align to present the viewer with equally scientific and fantastic renditions of natural history. Hailing from Hoorn and eventually dying in his hometown, Henstenburgh was a man of his surroundings who carefully copied and interpreted them to express their societal importance and ability to inspire.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend