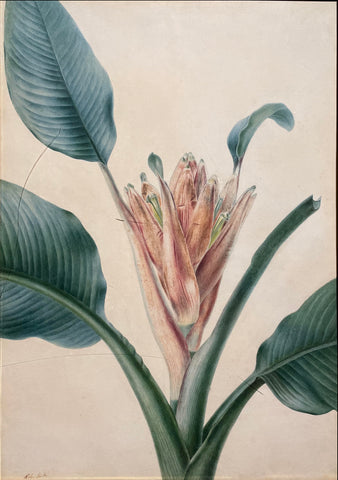

Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770), Pink Auricula

Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770)

Pink Auricula

Watercolor on vellum

Signed lower right: G.D. Ehret pinxt

ca. 1750

Paper size: 17 3/4 x 13 in

Frame size: 25 1/2 x 20 7/8 in

Pink Auricula

Watercolor on vellum

Signed lower right: G.D. Ehret pinxt

ca. 1750

Paper size: 17 3/4 x 13 in

Frame size: 25 1/2 x 20 7/8 in

These subtly splendid watercolors are by Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708-1770), arguably the finest flower painter of eighteenth-century Europe. Ehret’s work stands as a preeminent accomplishment of European botanical art, and the reasons for this acclaim are immediately evident in the virtuoso draftsmanship and fine, nuanced coloring of these works.

Born in Heidelburg to a market gardener, Ehret began his working life as a gardener’s apprentice, eventually becoming a chief gardener for the Elector of Heidelburg and the Margrave of Baden, whose prize tulips, and hyacinths he painted. Ehret soon moved on to several cities across Europe, collecting eminent friends and important patrons as he traveled. His list of benefactors included the most brilliant and celebrated natural history enthusiasts of his day, among whom was Dr. Christopher Trew, a wealthy Nuremberg physician who became his lifelong patron, friend, and collaborator. From 1750 until Ehret’s death in 1770, he and Trew collaborated on the publication of the important illustrated volumes Plantae Selectae and Hortus Nitidissimus, both of which added to the rising acclaim for the artist’s considerable talents as a botanical painter. Also, Ehret’s admirers were the Parisian naturalist Bernard de Jussieu and the great Swedish naturalist Linnaeus, and Ehret’s illustrations are some of the first works to reflect the Linnaean system of classification.

Ehret was one of the first artists to focus on exotic species from across the Atlantic, and his draftsmanship was so fine that his friend and colleague, the great artist/naturalist Mark Catesby, used at least three of the German painter’s botanical illustrations for his seminal Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. Today, Ehret’s images are widely considered the most desirable to emerge from that monumental publication, and he collaborated with Catesby in other ways, too, in the compilation of the Natural History, offering advice or adding significant elements to Catesby’s initial compositions. Catesby was influenced greatly by Ehret’s accomplished style, especially in the representation of three-dimensionality, but the older artist was never able to attain the same high level of meticulous realism and vitality. Ehret, in turn, drew on a few Catesby’s discoveries and observations in his own work. Unlike Catesby, Ehret was never able to travel to America but became fascinated with examples of New World flora that he saw in English natural history collections, such as that of Peter Collinson, a friend, and patron of both artists. Painted just at the time of the publication of Catesby’s Natural History, these watercolors are spectacular early representations of American flora.

In England, where he eventually settled, Ehret became the only foreigner to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Though Ehret’s work is best known through printed illustrations done in collaboration with Trew, even his impressive engravings cannot compare with the vibrancy, color, and detail of the original paintings. Only in his remarkably sensuous and accurate watercolors is the full extent of his mastery and sensitivity clear. Ehret’s delicate modulations of tone and shadow bring vitality to these exquisite original watercolors, belying their ostensibly documentary purpose. His distinctive style transcends scientific illustration, achieving a level of beauty that has rarely been equaled in the history of botanical art.

Born in Heidelburg to a market gardener, Ehret began his working life as a gardener’s apprentice, eventually becoming a chief gardener for the Elector of Heidelburg and the Margrave of Baden, whose prize tulips, and hyacinths he painted. Ehret soon moved on to several cities across Europe, collecting eminent friends and important patrons as he traveled. His list of benefactors included the most brilliant and celebrated natural history enthusiasts of his day, among whom was Dr. Christopher Trew, a wealthy Nuremberg physician who became his lifelong patron, friend, and collaborator. From 1750 until Ehret’s death in 1770, he and Trew collaborated on the publication of the important illustrated volumes Plantae Selectae and Hortus Nitidissimus, both of which added to the rising acclaim for the artist’s considerable talents as a botanical painter. Also, Ehret’s admirers were the Parisian naturalist Bernard de Jussieu and the great Swedish naturalist Linnaeus, and Ehret’s illustrations are some of the first works to reflect the Linnaean system of classification.

Ehret was one of the first artists to focus on exotic species from across the Atlantic, and his draftsmanship was so fine that his friend and colleague, the great artist/naturalist Mark Catesby, used at least three of the German painter’s botanical illustrations for his seminal Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. Today, Ehret’s images are widely considered the most desirable to emerge from that monumental publication, and he collaborated with Catesby in other ways, too, in the compilation of the Natural History, offering advice or adding significant elements to Catesby’s initial compositions. Catesby was influenced greatly by Ehret’s accomplished style, especially in the representation of three-dimensionality, but the older artist was never able to attain the same high level of meticulous realism and vitality. Ehret, in turn, drew on a few Catesby’s discoveries and observations in his own work. Unlike Catesby, Ehret was never able to travel to America but became fascinated with examples of New World flora that he saw in English natural history collections, such as that of Peter Collinson, a friend, and patron of both artists. Painted just at the time of the publication of Catesby’s Natural History, these watercolors are spectacular early representations of American flora.

In England, where he eventually settled, Ehret became the only foreigner to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Though Ehret’s work is best known through printed illustrations done in collaboration with Trew, even his impressive engravings cannot compare with the vibrancy, color, and detail of the original paintings. Only in his remarkably sensuous and accurate watercolors is the full extent of his mastery and sensitivity clear. Ehret’s delicate modulations of tone and shadow bring vitality to these exquisite original watercolors, belying their ostensibly documentary purpose. His distinctive style transcends scientific illustration, achieving a level of beauty that has rarely been equaled in the history of botanical art.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.com

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend