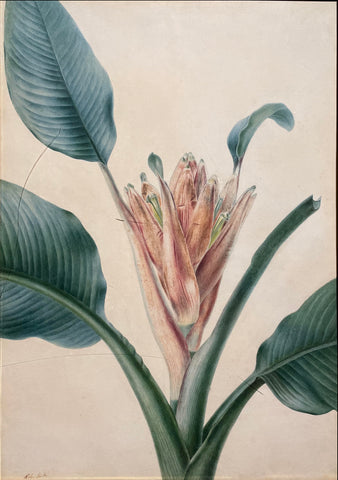

Maria Sibylla Merian (German, 1647-1717), Plate 30. Castor-oil Plant, Ricinis Butterfly, Unidentifiable Caterpillar and Greater Sacktail

Maria Sibylla Merian (German, 1647-1717)

“Plate 30. Castor-oil Plant, Ricinis Butterfly, Unidentifiable Caterpillar and Greater Sacktail”

from The Insects of Surinam

Watercolor and bodycolor with gum arabic over lightly etched outlines on paper

Amsterdam, 1705

Paper size: 20 x 14 in.

Transfer-print watercolors from The Insects of Surinam

According to Merian’s accounts, the oil from the castor-oil plant (Ricinis communis) was used in lamps as well as for the treatment of wounds in Surinam. “The ricinis butterfly (Eueides ricini) belong to the genus Heliconiidae, which comprises a number of known forms of the mimicry butterflies . . . The species designation assigned by Linné could derive from the fact that the butterflies tend to be drawn to the castor-oil plant; Linné may also have used this engraving by Merian for his description of the species.” The elongated insect between the blossom and the large leaf is the greater sacktail, which takes its name from the odd-looking protective envelope produced by the caterpillars from web material and leaf fragments. The position shown here is not typical; Merian forced the caterpillar to emerge as far as possible from its housing by squeezing the sack together. In her Studienbach, Merien noted that the caterpillars of the greater sacktail “hang like Indians in their hammocks, which they never completely abandon.” In this same work, Merian also mentioned that the unidentified caterpillar feeds on the castor-oil plant. On the other hand, the “ricini” caterpillars with their branching thorns live exclusively on passion-flowers, it is only the butterflies which prefer to sit on the castor-oil plant.

Descriptions of each plant adapted from J.Harvey’s commentary to the Folio Society facsimile of the Surinam Album (London, 2006) and Merian’s text for the Insects of Surinam.

One glimpse of any of Merian’s transfer-print watercolors from the Insects of Surinam reveals the main reasons for such celebration. Even to those who do not know of her work, this is a stunning sight. Her colors are alternately subtle and vibrant, capturing the quality of her subjects with striking naturalism. Yet while she maintains a scientist’s eye for precision, her creative decisions and compositions give these images a style that is distinctly hers. Each image demonstrates Merian’s masterful grasp of detail and nuance, as well as her outstanding ability to combine science and art. Equally significant, to early 18th century Europeans, her illustrations represented the first views of these American plants and insects.

These spectacular examples of her work are from one of a very few transfer-print watercolor volumes known to exist. Merian herself prepared the volume. After an uncolored print was made, she applied dampened paper to it, pressing by hand to create an image of the print in reverse. In this volume, she chose to block out the plate numbers and then add by hand, to some images, numbers, and notations. Merian then painstakingly watercolored the dried paper herself, ensuring that the colors were true to the specimens she had seen in South America, and also allowing her style to emerge with the greatest clarity. The volume was not meant for sale, and its intended purpose cannot be known with any certainty. Perhaps it was created as a gift for a wealthy and important patron, perhaps Merian meant to keep it herself. What can be stated without a doubt is that these splendid images represent a unique opportunity to acquire original works by an artist who broke barriers as a woman, as a scientist and artist, and whose accomplishments are no less impressive today than they were in her time.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend