![Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770), Xylon Americanum praestantis linum femine virescente. Lioen [American Cotton/Georgia Green Seed Cotton]](http://aradergalleries.com/cdn/shop/products/EH3A9F_1_large.jpg?v=1589570633)

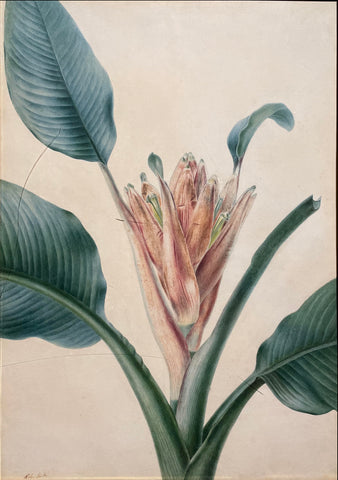

Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770), Xylon Americanum praestantis linum femine virescente. Lioen [American Cotton/Georgia Green Seed Cotton]

Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770)

Xylon Americanum praestantis linum femine virescente. Lioen

[American Cotton/Georgia Green Seed Cotton]

Watercolor on vellum

Signed G.D. Ehret pinxt

Vellum size: 17 ½ x 11 in.

[American Cotton/Georgia Green Seed Cotton]

Watercolor on vellum

Signed G.D. Ehret pinxt

Vellum size: 17 ½ x 11 in.

The importance of this image and the history of cotton in the Americas cannot be understated. It may well be one of the earliest images of American cotton.

Philip Miller describes five species of Cotton (Xylon) in his The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit and Flower Garden, as Also the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard, Volume 2, 1735. Stating of the Xylon Americanum praestantis linum femine virescente variety, “The most excellent American cotton, with a greenish seed.” The source of information was Tournefort via brothers Lignon who provided information on the botany of American islands and were apparently the original authors of the expression ‘the very excellent American cotton with green seeds.’ Miller continued to transcribe, the information furnished by the Lignons through the succeeding editions of the Dictionary down to the 6th (1752) where he made changes. Miller’s additional and more precise information regarding the plant was not likely to have been seen by Linnaeus in time for incorporation in the first edition of the ‘ Species Plantarum ‘ (1753), and in consequence G. hirsutum, Linn, was not published botanically until the second edition of the ‘ Species Plantarum ‘ (1763).

Miller corresponded at home and abroad with botanists, gardeners, and landowners. He introduced several rare and new species of plants through seed and plant exchange, instead of travel to foreign countries. He regularly received plants and seeds from America for the garden, particularly through his correspondence with John Bartram of Philadelphia, and exotics from such locations as the Cape of Good Hope, the Indies, and the Far East. Miller carefully imitated native conditions for the healthy growth of these new species at the garden, and his methods were reproduced in his books.

In 1732 Miller sent a package of the seeds of Xylon or Gossypium (cotton) species from the West Indies to improve the stock in the colony of Georgia, which would activate the south as the major player in the cotton industry. Urging that “it is well worthy the attention of the inhabitants of the British Colonies in America to cultivate and improve this sort.” Miller makes special mention of the wool of this species adhering firmly to the seeds, hence necessitating special gins. It was this difficulty that was finally overcome by Whitney in 1793, by the invention of the saw-gin. But to the frequent discussion of the firmly attached floss is due very possibly the error committed and perpetuated by several subsequent authors of describing the seeds as ‘adhering together.’ However difficult it was to harvest, the stock was superior to any cotton previously grown. That hint was apparently acted upon, for by 1786 the green-seeded cotton had become the sort chiefly grown in America.

Philip Miller’s friend and Ehret’s patron Peter Collinson had a specific interest in the growth of new commercial products in the colonies. Like Miller, he encourages colonists to grow cotton, hemp, and silk. This support of drapery material was not accidental. While Collinson was a prominent horticulturist, his trade was cloth. His customers were often wealthy landowners who, along with their ostentatious displays of wealth by dress, also sought to show their wealth through exotic plants which they grew in hothouses. Collinson grew these relationships in the colonies and too, befriending John Bartram and Benjamin Franklin. Because Collinson was tied into both worlds, he became a conduit between the colonies and these wealthy landowners often by way of seeds procured from his friends directly or by way of Miller. Collinson introduced Ehret to some of his first patrons including Margaret Cavendish Bentinck (1715-1785), Duchess of Portland.

Philip Miller describes five species of Cotton (Xylon) in his The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit and Flower Garden, as Also the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard, Volume 2, 1735. Stating of the Xylon Americanum praestantis linum femine virescente variety, “The most excellent American cotton, with a greenish seed.” The source of information was Tournefort via brothers Lignon who provided information on the botany of American islands and were apparently the original authors of the expression ‘the very excellent American cotton with green seeds.’ Miller continued to transcribe, the information furnished by the Lignons through the succeeding editions of the Dictionary down to the 6th (1752) where he made changes. Miller’s additional and more precise information regarding the plant was not likely to have been seen by Linnaeus in time for incorporation in the first edition of the ‘ Species Plantarum ‘ (1753), and in consequence G. hirsutum, Linn, was not published botanically until the second edition of the ‘ Species Plantarum ‘ (1763).

Miller corresponded at home and abroad with botanists, gardeners, and landowners. He introduced several rare and new species of plants through seed and plant exchange, instead of travel to foreign countries. He regularly received plants and seeds from America for the garden, particularly through his correspondence with John Bartram of Philadelphia, and exotics from such locations as the Cape of Good Hope, the Indies, and the Far East. Miller carefully imitated native conditions for the healthy growth of these new species at the garden, and his methods were reproduced in his books.

In 1732 Miller sent a package of the seeds of Xylon or Gossypium (cotton) species from the West Indies to improve the stock in the colony of Georgia, which would activate the south as the major player in the cotton industry. Urging that “it is well worthy the attention of the inhabitants of the British Colonies in America to cultivate and improve this sort.” Miller makes special mention of the wool of this species adhering firmly to the seeds, hence necessitating special gins. It was this difficulty that was finally overcome by Whitney in 1793, by the invention of the saw-gin. But to the frequent discussion of the firmly attached floss is due very possibly the error committed and perpetuated by several subsequent authors of describing the seeds as ‘adhering together.’ However difficult it was to harvest, the stock was superior to any cotton previously grown. That hint was apparently acted upon, for by 1786 the green-seeded cotton had become the sort chiefly grown in America.

Philip Miller’s friend and Ehret’s patron Peter Collinson had a specific interest in the growth of new commercial products in the colonies. Like Miller, he encourages colonists to grow cotton, hemp, and silk. This support of drapery material was not accidental. While Collinson was a prominent horticulturist, his trade was cloth. His customers were often wealthy landowners who, along with their ostentatious displays of wealth by dress, also sought to show their wealth through exotic plants which they grew in hothouses. Collinson grew these relationships in the colonies and too, befriending John Bartram and Benjamin Franklin. Because Collinson was tied into both worlds, he became a conduit between the colonies and these wealthy landowners often by way of seeds procured from his friends directly or by way of Miller. Collinson introduced Ehret to some of his first patrons including Margaret Cavendish Bentinck (1715-1785), Duchess of Portland.

These subtly splendid watercolors are by Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708-1770), arguably the finest flower painter of eighteenth-century Europe. Ehret’s work stands as a preeminent accomplishment of European botanical art, and the reasons for this acclaim are immediately evident in the virtuoso draftsmanship and fine, nuanced coloring of these works.

Born in Heidelburg to a market gardener, Ehret began his working life as a gardener’s apprentice, eventually becoming a chief gardener for the Elector of Heidelburg and the Margrave of Baden, whose prize tulips, and hyacinths he painted. Ehret soon moved on to several cities across Europe, collecting eminent friends and important patrons as he traveled. His list of benefactors included the most brilliant and celebrated natural history enthusiasts of his day, among whom was Dr. Christopher Trew, a wealthy Nuremberg physician who became his lifelong patron, friend, and collaborator. From 1750 until Ehret’s death in 1770, he and Trew collaborated on the publication of the important illustrated volumes Plantae Selectae and Hortus Nitidissimus, both of which added to the rising acclaim for the artist’s considerable talents as a botanical painter. Also, Ehret’s admirers were the Parisian naturalist Bernard de Jussieu and the great Swedish naturalist Linnaeus, and Ehret’s illustrations are some of the first works to reflect the Linnaean system of classification.

Ehret was one of the first artists to focus on exotic species from across the Atlantic, and his draftsmanship was so fine that his friend and colleague, the great artist/naturalist Mark Catesby, used at least three of the German painter’s botanical illustrations for his seminal Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. Today, Ehret’s images are widely considered the most desirable to emerge from that monumental publication, and he collaborated with Catesby in other ways, too, in the compilation of the Natural History, offering advice or adding significant elements to Catesby’s initial compositions. Catesby was influenced greatly by Ehret’s accomplished style, especially in the representation of three-dimensionality, but the older artist was never able to attain the same high level of meticulous realism and vitality. Ehret, in turn, drew on a few Catesby’s discoveries and observations in his own work. Unlike Catesby, Ehret was never able to travel to America but became fascinated with examples of New World flora that he saw in English natural history collections, such as that of Peter Collinson, a friend, and patron of both artists. Painted just at the time of the publication of Catesby’s Natural History, these watercolors are spectacular early representations of American flora.

In England, where he eventually settled, Ehret became the only foreigner to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Though Ehret’s work is best known through printed illustrations done in collaboration with Trew, even his impressive engravings cannot compare with the vibrancy, color, and detail of the original paintings. Only in his remarkably sensuous and accurate watercolors is the full extent of his mastery and sensitivity clear. Ehret’s delicate modulations of tone and shadow bring vitality to these exquisite original watercolors, belying their ostensibly documentary purpose. His distinctive style transcends scientific illustration, achieving a level of beauty that has rarely been equaled in the history of botanical art.

Born in Heidelburg to a market gardener, Ehret began his working life as a gardener’s apprentice, eventually becoming a chief gardener for the Elector of Heidelburg and the Margrave of Baden, whose prize tulips, and hyacinths he painted. Ehret soon moved on to several cities across Europe, collecting eminent friends and important patrons as he traveled. His list of benefactors included the most brilliant and celebrated natural history enthusiasts of his day, among whom was Dr. Christopher Trew, a wealthy Nuremberg physician who became his lifelong patron, friend, and collaborator. From 1750 until Ehret’s death in 1770, he and Trew collaborated on the publication of the important illustrated volumes Plantae Selectae and Hortus Nitidissimus, both of which added to the rising acclaim for the artist’s considerable talents as a botanical painter. Also, Ehret’s admirers were the Parisian naturalist Bernard de Jussieu and the great Swedish naturalist Linnaeus, and Ehret’s illustrations are some of the first works to reflect the Linnaean system of classification.

Ehret was one of the first artists to focus on exotic species from across the Atlantic, and his draftsmanship was so fine that his friend and colleague, the great artist/naturalist Mark Catesby, used at least three of the German painter’s botanical illustrations for his seminal Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. Today, Ehret’s images are widely considered the most desirable to emerge from that monumental publication, and he collaborated with Catesby in other ways, too, in the compilation of the Natural History, offering advice or adding significant elements to Catesby’s initial compositions. Catesby was influenced greatly by Ehret’s accomplished style, especially in the representation of three-dimensionality, but the older artist was never able to attain the same high level of meticulous realism and vitality. Ehret, in turn, drew on a few Catesby’s discoveries and observations in his own work. Unlike Catesby, Ehret was never able to travel to America but became fascinated with examples of New World flora that he saw in English natural history collections, such as that of Peter Collinson, a friend, and patron of both artists. Painted just at the time of the publication of Catesby’s Natural History, these watercolors are spectacular early representations of American flora.

In England, where he eventually settled, Ehret became the only foreigner to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Though Ehret’s work is best known through printed illustrations done in collaboration with Trew, even his impressive engravings cannot compare with the vibrancy, color, and detail of the original paintings. Only in his remarkably sensuous and accurate watercolors is the full extent of his mastery and sensitivity clear. Ehret’s delicate modulations of tone and shadow bring vitality to these exquisite original watercolors, belying their ostensibly documentary purpose. His distinctive style transcends scientific illustration, achieving a level of beauty that has rarely been equaled in the history of botanical art.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.com

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend