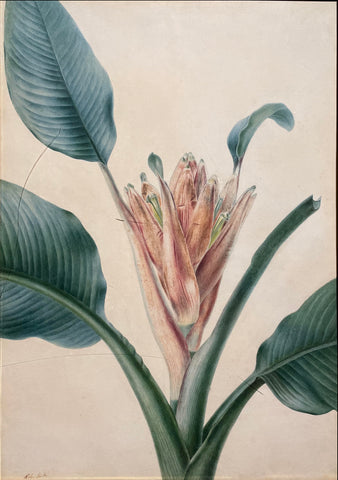

Pieter Holsteyn The Younger (Dutch, 1614-1687), Elleborus Niger

Pieter Holsteyn the Younger (dutch, 1614-1687)

Elleborus Niger

Watercolor on paper

Paper size: 12 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.

Helleborus niger, commonly called Christmas rose or black hellebore is a common European garden flower because of its heartiness through winter months. Although the flowers resemble wild roses (and despite its common name), Christmas rose does not belong to the rose family. In the wild, it is generally found in mountainous areas in Switzerland, southern Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia and northern Italy.

The black hellebore was described by Carl Linnaeus in volume one of his Species Plantarum in 1753. The Latin specific name niger (black) may refer to the color of the roots. It’s common name comes from a legend that it sprouted in the snow from the tears of a young girl who had no gift to give the Christ child in Bethlehem.

Black hellebore was the dominant purgative of antiquity, frequently prescribed for that purpose by Hippocrates, the father of medicine, in the fifth century B.C. It was said to be introduced by Melampus, with which he healed the madness of the daughters of Proteus, king of Argos.

Pieter Holsteyn the Younger, pupil of his father, practiced his art in his native Haarlem as well as at Zwolle and Munster. He painted in many media on canvas, glass, and vellum, and was also known for his engraved portraits. The market for still-life painting in Holland during the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries grew to the point where even moderate-sized towns often supported a small colony of artists. The specialization was not only one of style, but the subject matter as well. Holsteyn’s versatility and precision served him well in the painting of flowers, a subject of passionate interest during the period known as the Tulipomania.

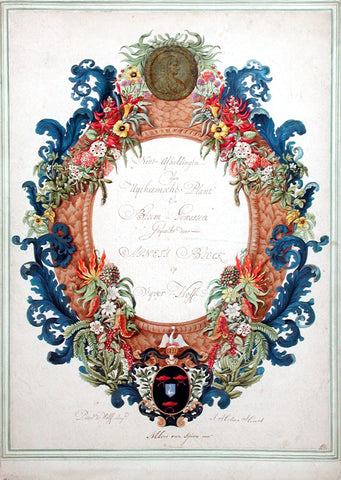

The tulip was introduced to Europe in 1552 by Charles Lecluse who bought seeds from Otto de Busbecq, the Austrian Ambassador to Turkey. The bulbs were started in Leyclen, the center of cultivation, and speculation drove the market for them with traders and wealthy collectors paying thousands of dollars for exotic specimens, especially the “broken” tulips with unusual markings. One contemporary pamphleteer arguing for the evils of the trade singled out that bulb by listing more useful goods, all of which could be purchased for the price of one bulb: two loads of wheat, four loads of rye, four fat oxen, eight fat pigs, twelve fat sheep, two hogsheads of wine, four barrels of beer, two barrels of butter, 1,000 pounds of cheese, a bed complete with bed linen, a suit of clothes and a silver beaker (together valued at 2,500 florins). The Brandemandus tulip book at the Stedelijk Museum he Prinsenhof in Delf includes annotations with prices achieved at a 1637 auction, with the Viceroy fetching 4200 guilders, among the highest valued bulbs in the sale. Even after the speculators’ market crashed in the late 1630s, these bulbs were still expensive and widely cultivated.

The “broken” tulip bloom is the kind that Holsteyn portrays so vividly several of the following watercolors, originally from a so-called “Tulip Book.” The albums were made for several reasons. Some were commissioned by wealthy gardeners, simply to record their treasures. Others were needed by commercial growers for their catalogues. There was also a demand by print publishers, who had a ready market for botanical prints. Finally, these portraits were often desired by other artists. The Dutch were famous for paintings of bouquets, which they embellished with rare and out-of-season flowers.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend