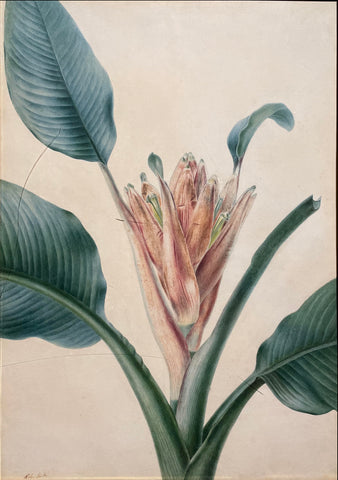

Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770), Magnolia altissima Laure Cerasa folio. flore ingenti Candide

Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770)

Magnolia altissima Laure Cerasa folio. flore ingenti Candide

Watercolor on vellum

Signed and dated ‘G.D. Ehret pinxt/1747’

Vellum size: 17 3/4 x 11 5/8 in.

Framed (modern) size: 21 3/8 x 27 3/8 in.

G.D. Ehret was unlike any other artist in Europe in the 18th century because he straddled the arts and sciences so dynamically as a conduit for seeds and information from botanists like Peter Collinson and Philip Miller to the father of modern taxonomy: Carl Linnaeus.

Painted in 1747, this unique image of the Magnolia altissima Laure Cerasa folio. flore ingenti Candide, commonly known as Magnolia Grandiflora, provides a unique link between art and science at a pivotal time in the development of botanical nomenclature. Shown in full bloom, the magnolia is placed on the page like a specimen plucked from the field and laid for an herbarium with leaves and petals shown from both sides as well as the fruit.

There are at least five Ehret watercolors of a magnolia grandiflora: Victoria & Albert Museum (dated 1743), Natural History Museum London (dated 1743), Natural History Museum London (two sketches 1746/47), a Private Collection (date unknown), and a composition of multiple blossoms at Oak Spring (undated.) All were executed from sketches made during Ehret’s meticulous study of the stages of growth at a specimen tree at Charles Wager’s property at Parsons Green. In the summer of 1737, Ehret walked around three miles several times a week to draw Wager’s magnolia, one of the first to bloom in the country, in various stages of growth and then decay.

Given the concentrated study of the plant in the late 1730s, why the proliferation of images in the early 1740s? The winter of 1740 and 1741 were some of the coldest experienced in England. February of 1740 averaged only 7 degrees. Therefore, any magnolia trees that had managed to blossom succumbed to frost giving Ehret no examples to consult further. Peter Collinson called the season of loss “a trying time to our gardens.” By 1742 or so England was seeing regrowth of this extraordinary ornamental plant.

Starting in 1736, Ehret not only provided seeds but drawings and observations to Linnaeus. Linnaeus would sometimes request certain plants, thanking Ehret for “incomparably beautiful illustrations of new plants” and encouraging him “your talent which makes you outstanding in the botanical world.” The scientist was particularly interested in “new and strange plants” and seeds which Ehret was procuring from the Americas via Miller. As for the magnolia, Ehret brought the plant up to him as early as 1738 telling him “he would have loved to send him a drawing of the magnolia but did not have a chance to do so.” In 1747, the year of the present watercolor, we see the magnolia return to the topic of conversation between the two. On August 23, 1747, Linnaeus writes to Ehret: “My dear friend, I am very grateful for the wonderful gifts that you sent me. It is a shame that I have never been able to reciprocate your numerous services, especially since I am living far away. Everyone admires your drawings and your talent. I have received your Cereus Minimus, Agaricus Ramosus, and Magnolia which are masterpieces.” And, follows up with another letter in October of 1747, “I owe you a thousand thanks for your friendship and the wonderful pictures that you have sent me for years. They are precise and beautiful and they adorn my walls of my study where visitors are amazed by their quality.”

The two were a finely tuned working team and Linnaeus had the greatest regard for his work, greeting him in a letter of 1759, “To the Apelles of flowers himself, my old friend Dionysius Ehret whom I, Linnaeus, express many greetings.” That same year, Linnaeus named this plant Magnolia Grandiflora.

We Also Recommend