Francois Van Boeckholtz (Dutch, fl 1773 - 1819), Korte beschreiving van den Soekoon, of Brood=boom op Java.

Francois Van Boeckholtz (Dutch, fl 1773 - 1819)

Korte beschreiving van den Soekoon, of Brood=boom op Java.

Samarang: 1794

Korte beschreiving van den Soekoon, of Brood=boom op Java.

Samarang: 1794

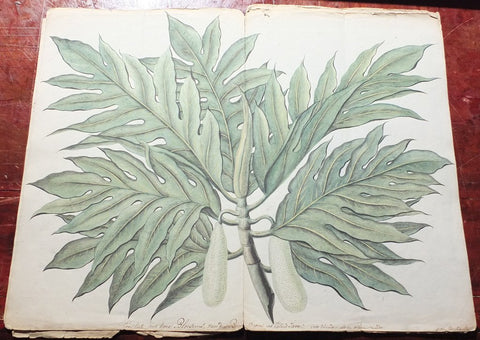

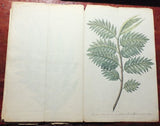

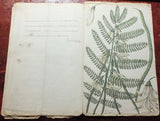

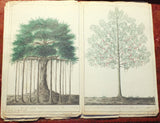

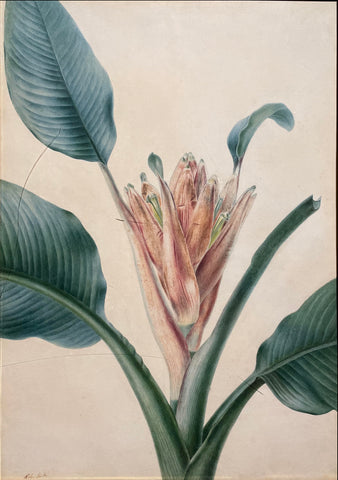

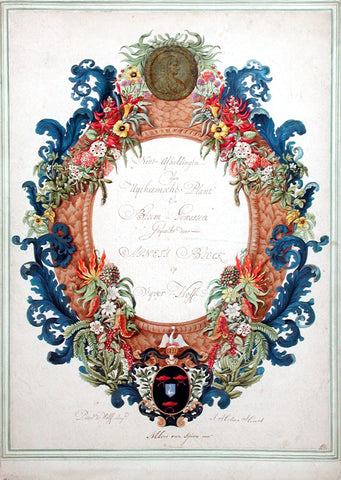

Folio (13 x 8 in.). 4-pages of close manuscript in Dutch in a clerical hand with annotations by Boeckholtz. Fine double-page original watercolor drawing of a Breadfruit branch, and 8 full-page watercolor drawings of the Breadfruit tree, it’s leaves, a Banyan tree, and a Flame tree and it’s leaves, flowers and fruit, on 12 pages, each captioned by and signed by Boeckholtz, all on Pro Patria “Hollandia” laid paper. Never bound.

A MAGNIFICENT suite of nine original watercolour drawings of the important Javanese breadfruit tree, the iconic Banyan tree and Flame tree, by FRANCOIS VAN BOECKHOLTZ, THE LAST VOC GOVERNOR OF BANDA, and the pioneering archaeologist of ancient Java. Boeckholtz, who wrote several articles and a book on the history of Java and its natural history, and was a contributor to Sir Stamford Raffles’ History of Java, published in 1817.

“regarding food, if a man plant 10 (breadfruit) trees in his life he would completely fulfill his duty to his own as well as future generations…” Sir Joseph Banks, 1769

Breadfruit has been an important staple crop in the Pacific - southeast Asian region for more than 3,000 years. It is thought to have originated in New Guinea and the Indo-Malay area and was spread throughout the vast Pacific region by ocean-going islanders. Europeans discovered breadfruit in the 1500s and were immediately attracted to the potential of the prolific, starchy fruits that, when roasted, resembled freshly baked bread.

Breadfruit is known throughout the world for its association with the infamous “Mutiny on the Bounty”. In 1789 William Bligh lost his ship Bounty to mutineer Fletcher Christian and his supporters on the voyage back to England from Tahiti, where the Bounty had been commissioned by George III at the suggestion of Sir Joseph Banks, to collect breadfruit. The object of the expedition had been to transport the nutritious, fast-growing fruit to the West Indies for propagation as a cheap food for slave laborers who worked the vast sugar estates. The breadfruit of Java would have been unattainable to the Bligh expedition while it was still a Dutch colony.

A MAGNIFICENT suite of nine original watercolour drawings of the important Javanese breadfruit tree, the iconic Banyan tree and Flame tree, by FRANCOIS VAN BOECKHOLTZ, THE LAST VOC GOVERNOR OF BANDA, and the pioneering archaeologist of ancient Java. Boeckholtz, who wrote several articles and a book on the history of Java and its natural history, and was a contributor to Sir Stamford Raffles’ History of Java, published in 1817.

“regarding food, if a man plant 10 (breadfruit) trees in his life he would completely fulfill his duty to his own as well as future generations…” Sir Joseph Banks, 1769

Breadfruit has been an important staple crop in the Pacific - southeast Asian region for more than 3,000 years. It is thought to have originated in New Guinea and the Indo-Malay area and was spread throughout the vast Pacific region by ocean-going islanders. Europeans discovered breadfruit in the 1500s and were immediately attracted to the potential of the prolific, starchy fruits that, when roasted, resembled freshly baked bread.

Breadfruit is known throughout the world for its association with the infamous “Mutiny on the Bounty”. In 1789 William Bligh lost his ship Bounty to mutineer Fletcher Christian and his supporters on the voyage back to England from Tahiti, where the Bounty had been commissioned by George III at the suggestion of Sir Joseph Banks, to collect breadfruit. The object of the expedition had been to transport the nutritious, fast-growing fruit to the West Indies for propagation as a cheap food for slave laborers who worked the vast sugar estates. The breadfruit of Java would have been unattainable to the Bligh expedition while it was still a Dutch colony.

Francois Van Boeckholtz (Dutch, fl 1773 - 1819)

Boeckholtz of “Vooren”, is recorded as arriving in Batavia in July of 1774, as a sergeant with the ship “Gratitude”. He was Second Resident, secretary, and pay bookkeeper of Surakarta between 1783 and 1789. Importantly he was the last VOC Governor of Banda between 1794 and 1796, when Banda was captured by the British in HMS Amboyna in early March.

The attribution of Van Boeckholtz’s drawings and his archaeological work is discussed by Roy Jordaan in his “The Lost Gatekeepers Statues of Candi Prambanan: A Glimpse of the VOC Beginnings of Javanese Archaeology”:

‘Francois van Boeckholtz was the VOC’s Second Resident at Surakarta. Earlier as a Lieutenant he was stationed in Salatiga, where he started making drawings of Hindu antiquities ‘although ignorant in archaeology’ (de Haan 1935:503)... As chance would have it, van Boeckholtz as Second Resident of Surakarta, later would have to escort Reimer and the other members of the Military Commission from Semarang to south central Java and facilitate their official reception at Surakarta (see NA 1.10.03, Collection Alting, inventory number 87). It could not be established whether van Boeckholtz also escorted this company during the second stretch of their journey to Jogjakarta... Excerpts of various notices (but not on archaeology in a strict sense) by van Boeckholtz can be found in the early issues of the Proceedings of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences (Boeckholtz 1814, 1816). He is the author of a comprehensive, if unfinished manuscript on the island of Java entitled Beschrijving van het Eyland Groot Java (KITLV holding DH457). A copy and an English translation as Historical Account of the Island of Great Java were prepared for Colin Mackenzie in 1814 (see MSS. Eur Mack Priv 16). Conceivably, van Boeckholtz’s unpublished work inspired the studies by Raffles (1817) and Crawfurd (1820), in addition to William Marsden’s History of Sumatra (1783) and other influences (see Bastin 2004:11, 31)... Some of van Boeckholtz’s drawings, originals and copies, ended up in the Mackenzie and the Raffles Collections, partly in the British Library and partly the British Museum. Comparison of the handwriting of the captions with the handwritings of van Boeckholtz, Engelhard, and Cornelius (or members of his team) respectively, could yield further clues as to the identity of the draughtsman of the catalogue drawings. My own comparisons lead me to support Gallop’s suggestion that the handwriting in the caption of drawing no. 1 is that of van Boeckholtz (NSC Working Paper No. 14, September 2013, Notes 30 and 31)’. Drawings by Francois van Boeckholtz of a kneeling guardian statue and of ‘Embo Lorro Djongrang’ are in the British Museum”.

During the course of the 18th century the United East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, abbreviated VOC) had established itself as the dominating economic and political power on Java after the disintegration and collapse of the Mataram empire.

Lontor, Bandaneira, Run, Ai and Rozengain in the sothern Moluccas “were the only producers of mace and nutmeg. It was on these islands that Jan Pietersz. Coen wreaked a gruesome havoc in 1621 and had nearly the entire indigenous population murdered or driven away. The rivalry with the English reached its peak in 1623 when, based on a rumor of a conspiracy against the Dutch, all of the Englishmen on the island of Run were put to death. The massacre was the source of much friction between the Netherlands and England for a long time after, but it did put an end to the English influence in the Moluccas. From that time onward, the two mighty forts of Belgica and Nassau protected the VOC’s mace and nutmeg monopoly. After the bloody conquest, the VOC established a plantation on the Banda islands.

“The policy of the VOC was directed at safeguarding the monopolies of Ambon and Banda islands. In order to achieve this goal, the Dutch had also established themselves in the northern Moluccas. The felling of the wild nutmeg and clove trees, for which the Dutch concluded contracts with the indigenous sovereigns, was overseen from Fort Oranje on Ternate” (Gunter Schilder & Hans Kok “Sailing for the East”, page 52).

Mismanagement, corruption and fierce competition from the English East India Company, however, resulted in the slow demise of the VOC towards the end of the 18th century. In 1796 the VOC went bankrupt and was nationalized by the Dutch state. As a consequence its possessions in the archipelago passed into the hands of the Dutch crown in 1800. However, when the French occupied Holland between 1806 and 1815 these possessions were transferred to the British. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo it was decided that most parts of the archipelago would return to the Dutch.

Another example of this manuscript can be found in the Bancroft Library at UC, Berkeley: Boeckholtz, F. van. Korte beschreiving van den soekoon, of broodboom op Java, BANC MSS 92/566 z, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

The attribution of Van Boeckholtz’s drawings and his archaeological work is discussed by Roy Jordaan in his “The Lost Gatekeepers Statues of Candi Prambanan: A Glimpse of the VOC Beginnings of Javanese Archaeology”:

‘Francois van Boeckholtz was the VOC’s Second Resident at Surakarta. Earlier as a Lieutenant he was stationed in Salatiga, where he started making drawings of Hindu antiquities ‘although ignorant in archaeology’ (de Haan 1935:503)... As chance would have it, van Boeckholtz as Second Resident of Surakarta, later would have to escort Reimer and the other members of the Military Commission from Semarang to south central Java and facilitate their official reception at Surakarta (see NA 1.10.03, Collection Alting, inventory number 87). It could not be established whether van Boeckholtz also escorted this company during the second stretch of their journey to Jogjakarta... Excerpts of various notices (but not on archaeology in a strict sense) by van Boeckholtz can be found in the early issues of the Proceedings of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences (Boeckholtz 1814, 1816). He is the author of a comprehensive, if unfinished manuscript on the island of Java entitled Beschrijving van het Eyland Groot Java (KITLV holding DH457). A copy and an English translation as Historical Account of the Island of Great Java were prepared for Colin Mackenzie in 1814 (see MSS. Eur Mack Priv 16). Conceivably, van Boeckholtz’s unpublished work inspired the studies by Raffles (1817) and Crawfurd (1820), in addition to William Marsden’s History of Sumatra (1783) and other influences (see Bastin 2004:11, 31)... Some of van Boeckholtz’s drawings, originals and copies, ended up in the Mackenzie and the Raffles Collections, partly in the British Library and partly the British Museum. Comparison of the handwriting of the captions with the handwritings of van Boeckholtz, Engelhard, and Cornelius (or members of his team) respectively, could yield further clues as to the identity of the draughtsman of the catalogue drawings. My own comparisons lead me to support Gallop’s suggestion that the handwriting in the caption of drawing no. 1 is that of van Boeckholtz (NSC Working Paper No. 14, September 2013, Notes 30 and 31)’. Drawings by Francois van Boeckholtz of a kneeling guardian statue and of ‘Embo Lorro Djongrang’ are in the British Museum”.

During the course of the 18th century the United East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, abbreviated VOC) had established itself as the dominating economic and political power on Java after the disintegration and collapse of the Mataram empire.

Lontor, Bandaneira, Run, Ai and Rozengain in the sothern Moluccas “were the only producers of mace and nutmeg. It was on these islands that Jan Pietersz. Coen wreaked a gruesome havoc in 1621 and had nearly the entire indigenous population murdered or driven away. The rivalry with the English reached its peak in 1623 when, based on a rumor of a conspiracy against the Dutch, all of the Englishmen on the island of Run were put to death. The massacre was the source of much friction between the Netherlands and England for a long time after, but it did put an end to the English influence in the Moluccas. From that time onward, the two mighty forts of Belgica and Nassau protected the VOC’s mace and nutmeg monopoly. After the bloody conquest, the VOC established a plantation on the Banda islands.

“The policy of the VOC was directed at safeguarding the monopolies of Ambon and Banda islands. In order to achieve this goal, the Dutch had also established themselves in the northern Moluccas. The felling of the wild nutmeg and clove trees, for which the Dutch concluded contracts with the indigenous sovereigns, was overseen from Fort Oranje on Ternate” (Gunter Schilder & Hans Kok “Sailing for the East”, page 52).

Mismanagement, corruption and fierce competition from the English East India Company, however, resulted in the slow demise of the VOC towards the end of the 18th century. In 1796 the VOC went bankrupt and was nationalized by the Dutch state. As a consequence its possessions in the archipelago passed into the hands of the Dutch crown in 1800. However, when the French occupied Holland between 1806 and 1815 these possessions were transferred to the British. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo it was decided that most parts of the archipelago would return to the Dutch.

Another example of this manuscript can be found in the Bancroft Library at UC, Berkeley: Boeckholtz, F. van. Korte beschreiving van den soekoon, of broodboom op Java, BANC MSS 92/566 z, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.com

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend