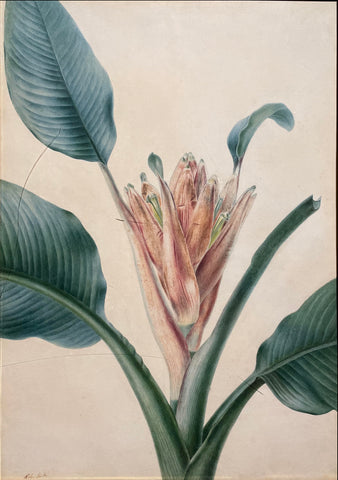

ANN LEE (BRITISH, 1753–1790), Curcuma Longa (Turmeric)

ANN LEE (BRITISH, 1753–1790)

Curcuma Longa (Turmeric)

Watercolor and pencil on vellum

Inscribed “Ann Lee September 1, 1772” l.l.

Paper size: 18 ¼ x 12 ¾ in.

Framed size: 26 ½ x 21 ½ in.

Provenance: Private collection, England.

This is a beautiful painting of the spice turmeric created by Ann Lee in September 1772. The painting displays an early understanding of the sexual system of plants, as shown in the lower right-hand corner, indicating a clear knowledge of Linnaean nomenclature beyond just the attractive illustration. Ann must have observed this plant in a controlled environment aided by a stove, as this species could not survive in the English climate. The species was described by Philip Miller in his 1768 Gardener's Dictionary.

“These plants grow naturally in India, from whence the roots are brought to Europe for use. They are very tender, it will not live in this country, unless they are placed in a warm stove. As they do not produce seeds in England, they are only propagated by parting their roots: the bell time for removing and parting these roots is in the spring, before they put out new leaves -, for the leaves of these plants decay in autumn, and the roots remain inactive till the spring, when they put out fresh leaves. The roots should be planted in rich kitchen-garden earth, and the pots should be constantly kept plunged in a bark-bed in the stove. In the summer season, when the plants are in a growing state, they will require to be frequently refreshed with water, but it should not be given to them in large quantities; they should also have a large share or air admitted to them in warm weather. When the leaves are decayed, they should have very little wet, and must be kept in a warm temperature of air, otherwise they will perish.

These plants usually flower in August, but it is only the strong roots which flower, so they must not be parted into small roots, where the flowers are desired.”

Ann Lee (1753-1790), an artist-naturalist, made significant contributions to the fields of art and science through her drawings of plants, birds, and insects. She was not only the daughter of nurseryman James Lee but also a botanist, entomologist, and artist. Ann grew up at the center of English botanical culture in her father's nursery, The Vineyard Nursery, a thriving establishment known for introducing exotic plants from different parts of the world into English gardens.

Ann had a unique opportunity to learn the artistic and scientific necessity of botanical painting, which was encouraged by her father and his associates, including Joseph Banks. She received training from Sydney Parkinson, the celebrated artist who worked as a draughtsman with the Vineyard from about 1766-67 and inherited Parkinson's painting instruments after his death.

Ann's drawings are highly accurate and are rare early examples of incorporating the Linnaean system. She likely observed valuable meetings at her father's nursery with botanists like Joseph Banks, who had direct connections to Carl Linnaeus and his new system, which would have been discussed and implemented at the garden. James, Ann's father, published the first English translation of Linnaeus' work in 1760.

Danish naturalist Johann Fabricius considered Ann the best natural history painter in England. She received commissions to draw exotics in the botanical garden of some of the most important botanists of the period, including Dr. John Fothergill.

Ann made a significant contribution to scientific study in her short life. An image of the proper pinning of insects for successful preservation for transport over a long distance published in John Ellis's (c.1710-1776) Directions for Bringing Over Seeds and Plants was drawn by Ann Lee, which was the primary way that naturalists learned the proper pinning technique.

Although Ann died young at the age of thirty-seven, her substantial collection of drawings now forms the Ann Lee Collection at Kew Gardens. Most of her paintings were passed down through the family, and she did not receive credit for those translated to print, which accounts for her delegation to obscurity until recently.

We Also Recommend