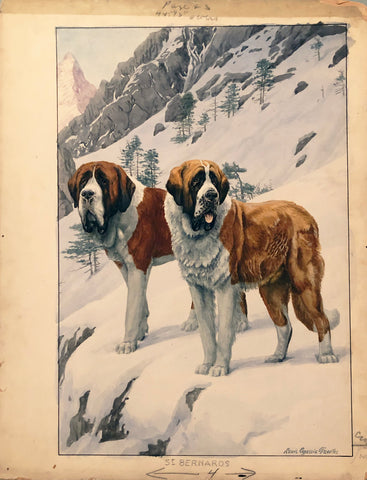

LOUIS AGASSIZ FUERTES (AMERICAN, 1874-1927), St. Bernards

LOUIS AGASSIZ FUERTES (AMERICAN, 1874-1927)

“St. Bernards”

Original watercolor prepared for The Book of Dogs: An Intimate Study of Mankind’s

Best Friend. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1919.

Watercolor and gouache on board

Board size: 16 x 13 in.

Inventory #AP02586

Fuertes wrote, “The St. Bernard won both his name and his fame in the Swiss Alps, where for many years the monks of the Hospice St. Bernard have used dogs to assist them in saving the lives of travelers lost in the snow. One of these dogs, Barry, saved 40 people and was killed by the 41st, who mistook him for a wolf. But the dogs used by the monks have changed greatly in appearance from time to time. Occasionally an avalanche will destroy a large number, and those remaining will be bred to Newfoundlands, Pyrenean sheep dogs, and others having similar characteristics. Some of the dogs kept at the hospice now resemble powerful foxhounds and would never be admitted to an American bench show in competition with modern St. Bernards, cither smooth or rough coated, such as are pictured on page 51. The old-time working hospice dog had none of the grandeur of this more modern successor to his name, which has been compounded rather recently of several other dogs. Still he is about the most distinct of any of the large dogs, the Newfoundland being the only dog even remotely resembling him. Like all very large heavy dogs, this breed is greatly given to weakness in the legs, cowhocks and weak hips being rather the rule than the exception. The “dewclaw,” or extra hind toe, is also generally present (and was formerly considered desirable). The perfect St. Bernard is a very large, very strong, straight-backed, strong-legged, and heavily organized dog, the colors, as shown, being those most eagerly sought. They may be either rough or smooth in coat. The best American dogs are those of Mr. Jacob Rupert, of Newark, N. J., and Miss C. B. Trask, of California. Indeed, it is doubtful if their dogs are to be surpassed anywhere. The benign St. Bernard should show, in both types, broad, domed, massive head, loose skin, deep-set, rather mournful, eye, haw quite pro nounced, and deep-folded flews and dewlap, though he should not be too “throaty.” What is not mentioned in most brief accounts of this dog is the tremendously impressive voice in which he speaks. Probably no other dog has such a deep bass voice, nor such a volume of it. Yet it is as benign and kindly as his ex pression of countenance, and would tend rather to inspire hope and confidence than fear, even with the timid. The deep personal affection with which St. Bernard owners invariably invest their companions is the best expression of the character of these great, dignified and rather somber dogs, which inspire no fear, even in little children, and which return the stranger’s gaze with a look of calm, steady, and indulgent tolerance, and endure the advances of the unacquainted with a patience and dignity that speak worlds for their gracious and enduring disposition.”

Original watercolors prepared by Louis Agassiz Fuertes for The Book of Dogs: An Intimate Study of Mankind’s Best Friend. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1919.

Fuertes’ intention was plainly laid out in the introduction to this beautifully illustrated work. Writing, “The dog is a species without known beginning, and of all man’s dependent animals the most variable in size, form, coat, and color.…The illustrator’s problem in preparing this series was not the production of a ‘standard of perfection’ of the various “breeds” of dogs. It was to give, as far as possible, the proper appearance of acceptable types that have been dignified by a name, and to show in what way they are entitled to the friendship and care and companionship of man. Let it not be thought that it was an easy task, nor that had time, opportunity, early concentration, and a larger acquaintance with the field been part of the artist’s equipment, the result would not have been far more satisfactory to the reader and to him… If these pictures it has been less his notion to establish types and a pictorial standard than to show the “man on the street” the general appearance and the special reason for being of the seventy- odd “kinds” of dogs that seemed to the editor and the artist best included in such an exposition as this. There are, of course, other recognized varieties of dogs, but those shown are the kinds best known.”

Fuertes relied on readily available titles such as Leighton’s “Book of the Dog” and Watson’s “Dog Book” (first 2 vol. ed.) to “Field and Fancy,’’ and to the illustrated supplements to “Our Dogs,” as well as photographs provided to him from various kennels and helpful men and women known to him. From which he created these charming canine illustrations.

We Also Recommend