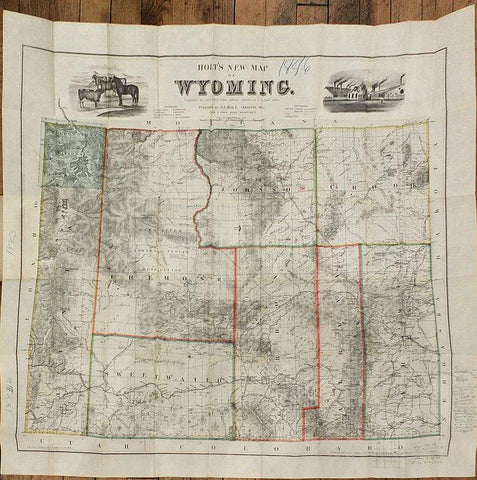

George L. Holt, Holt's New Map of Wyoming. Compiled by permission from official records in U.S. Land Office.

George L. Holt

Holt's New Map of Wyoming. Compiled by permission from official records in U.S. Land Office.

Published by G.L.Holt, Cheyenne, Wyo: Frank & Fred Bond, Draftsmen, 1886

Sheet size: 28 2/8 x 31 in.

Lithograph, with original hand-colour in outline, the title across the top of the map between fine vignettes of livestock and a meat-packing factory, engraved & printed by G.W. & C.B. Colton, New York. Tipped into original brown cloth, gilt, wallet.

Provenance: annotated in pencil in the margins by someone who seems to have owned parcels of land in Wyoming, and dated with wax crayon 1886 in the margin.

Fourth issue, first published in 1883, this issue with Fremont county and the change in boundary between Albany and Carbon counties. A very fine and detailed map of Wyoming, showing individual residences, ranches, forts, Indian reservations, mining districts, railroads, stage roads, and regular roads. There were five issues of this map: 1883, 1884, 1885, 1886, and 1888. Between 1841 and 1860, roughly 350,000 people crossed what is now Wyoming on the Oregon Trail. This demand for sustenance, mild winters that allowed ranchers to overwinter their livestock outside, the fact that railroad surveyors decided to route the Union Pacific through Cheyenne, not Denver, combined to create a booming cattle industry in Wyoming.

A state of affairs reflected in the vignettes at the top of the map. Ironically the cattle boom was all but over by the time this issue of Holt's map was published: "There were too many cows. Wyoming historian T.A. Larson estimated that by 1886 there were 1.5 million cattle (about the same number Wyoming has now) on the range. The weather turned crispy dry in the summer and iron cold in the winter. A drought that began in Texas in the summer of 1884 crept north. By 1886, eastern Wyoming and Montana were the driest in memory. By September of that year, some parts of Montana had received just two inches of rain. "In his annual report of 1886, the commander of Fort McKinney near Buffalo, Wyoming Territory, wrote, "The country is full of Texas cattle and there is not a blade of grass within 15 miles of the Post." The beef bubble popped. By November 1886, wholesale cattle prices in Chicago fell to $3.16 per hundredweight, half of what they had been in 1884. The winter of 1886-87 was known as the "death knell on the range." Snow came early and stayed.On Jan. 14, 1887, temperatures in Miles City, Mont., bottomed out at 60 below zero. The Laramie Daily Boomerang of Feb. 10, 1887, reported, "The snow on the Lost Soldier division of the Lander and Rawlins stage route is four feet deep, and frozen so hard that the stages drive over it like a turnpike.""Historians generally agree that Wyoming cattle losses during that winter tend to be exaggerated. Larson thought overall the state lost about 15 percent of its herd, although operators in Crook and Carbon counties lost roughly 25 percent of their stock. John Clay wrote in My Life on the Range, "As the South Sea bubble burst, as the Dutch tulip craze dissolved, this cattle gold brick withstood not the snow of winter. It wasted away under the fierce attacks of a subarctic season aided by summer drought. For years, you could wander amid the dead brushwood that borders our streams. In the struggle for existence the cattle had peeled off the bark as if legions of beavers had been at work." (Wyoming State Historical Society online). W-TW 1302. Streeter 2254.

We Also Recommend