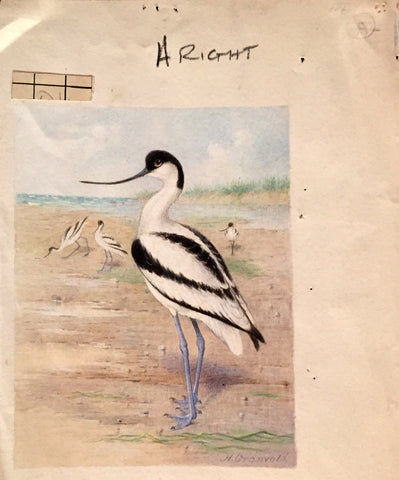

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Recurvirostra Avocetta (Avocet)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Recurvirostra Avocetta (Avocet)”

Prepared for Plate V W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper or card

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.r.

1922-1923

Paper size: 7 1/4 x 6 5/8 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“A handsome black and white bird to which the long, slender, upturned bill gives a somewhat singular appearance. On account of this form of bill it was locally called ‘Shoe-awl,’ and ‘Shoeing-horn’; also, it was known as the Telper, Barker, Clinker, in allusion to its shrill barking note. In habits it is social, lively and playful, and feeds in a curious way, the birds moving on in an even row, swaying their bodies from side to side, with bills immersed in the shallow water; the action reminding one of a row of mowers mowing a field of grass.

It used to breed in considerable numbers on the sandy flats of the east coast from Yorkshire to Sussex, and especially in Norfolk. It practically ceased to breed in England between the years 1822 and 1825, but one or two later records are given on local authority.

In Plomley’s time, says Ticehurst’s History of the Birds of Kent (1909) the bird was fast disappearing as a breeding species, though still not uncommon (meaning, probably, as a migrant). Plomley had four birds in his collection and could have procured many more. A nest of young was found, he adds, in 1842, and in the succeeding year he killed two young birds on the wing. Two of the birds in Plomley’s collection, adds Dr. Ticehurst, were shot in April 1841, and ‘are of special interest as being probably the only representatives still in existence of the original Romney Marsh Avocets.’ They are in Dover Museum. The 1844 record ‘contains the final mention of a nest in the county of Kent, and by the spring of 1849 we find the first reference to the breeding Avocet as a thing of the past.’ It is still a visitor to the Kentish coast.

Nelson in his Birds of Yorkshire (1907) claims the last known nest for his own district. ‘The latest known instance of the Avocet nesting in Britain was in the mouth of the Trent, about the year 1837. Hugh Reid of Doncaster informed A. G. More in a letter dated 1st January, 1861, that eggs were taken on a sand island at the mouth of the River Trent about twenty-four years before. There was at the time a spring tide which nearly covered the island and the eggs were floating on the water. The man who took them shot one of the parent birds at the same time. . . The county boundary being at this place drawn in the centre of the river, Yorkshire will share with Lincolnshire the honour of possessing the last British breeding station of the Avocet.’ The honour of exterminating the British species is therefore grasped at by both counties. The most recent record of the bird in Yorkshire at the time Nelson wrote was April, 1839, when two were seen at Flamborough Lighthouse and were duly ‘procured’ and ‘stuffed.’

Stevenson (Birds of Norfolk) says: At Salthouse, long prior to the drainage of the marshes and the erection of a raised sea-bank, the Avocets had become exterminated by the same wanton destruction of both birds and eggs as is yearly diminishing the numbers of Lesser Terns and Ringed Plover of the adjacent banks.

Of former times Stevenson writes: I have conversed with an octogenarian fowler and marshman, named Pigott, who remembered the ‘Clinkers’ (as the Avocet was there called) breeding in the marshes by the hundreds, and used constantly to gather their eggs. Mr. Dowell, also, was informed by the late Harry Overton, a well-known gunner in that neighbourhood, that in his young time he used to gather the Avocets’ eggs, filling his cap, coat-pockets, and even his stockings; and the poor people thereabouts made puddings and pancakes of them. The birds were also as recklessly destroyed, for the gunners, to unload their punt guns, would sometimes fire at and kill ten or twelve at a shot. No wonder, then, if the Avocets, thus constantly persecuted, gradually became scarce.

In his handbook of The Birds of the British Isles (1920) Mr. Coward comments: ‘The too conspicuous Avocet is indeed a ‘ lost British bird/’ having been once a regular summer visitor and become now a rare spring and autumn migrant; but he adds that some of these spring visitors might even now remain and breed if allowed. ‘But the bird is slain whenever it is seen. For instance, a party of seven were seen at St. Leonards and within a few hours four were taken to a taxidermist’s.’ Only where they are protected, he adds, are there any records of the birds seen and not shot. Protected by an active and agile Watcher, is, of course, implied. The fact that the species is fully protected by the Wild Birds Protection Act no doubt increases the satisfaction of those who have succeeded in adding the slain birds to their collections. People who take pleasure in the possession of such remains as birds’ feathers, bones, and egg-shells, are always glad to secure an Avocet.’

‘Some years ago, I was told that more than twenty specimens were received at Leadenhall Market for sale, within one month. But now scarcely an example appears in a year.’— Yarrell’s British Birds.

‘This remarkable bird was formerly a regular summer visitor to our shores, breeding in considerable numbers in such suitable localities as the coast and estuaries of the Humber district, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk. Reclamation of fenland gradually circumscribed its haunts; a large colony at Salthouse was destroyed, as Mr. J. H. Gurney was informed, in consequence of the demand (especially from Newcastle) for Avocet’s feathers for dressing artificial flies; and egg collectors also contributed to the decrease of the species, which by 1824 had probably ceased to nest in England. Small flocks still arrive in May, and occasionally in autumn, but the former are never allowed to breed, for the amasser of British-killed specimens offers to British gunners inducements which far exceed the amount of any fine and costs that could be imposed, even in the problematical event of the offender’s conviction. On the south coast the Avocet used to nest on the flat shores of Kent, and Sussex, to which it is now only a visitor.’— Saunders’s Manual.

‘This species was of old time plentiful in England, though doubtless always restricted to certain localities. Charleton in 1668 says that when a boy he had shot not a few on the Severn, and Plot mentions it so as to lead one to suppose that in his time (1686) it bred in Staffordshire, while Willughby (1676) knew of it as being in winter on the east coast, and Pennant in 1769 found it in great numbers opposite to Fossdyke Wash in Lincolnshire, and described the birds as hovering over the sportsman’s head like Lapwings. In this district they were called ‘yelpers’ from their cry; but whether that name was elsewhere applied is uncertain. At the end of the last century they frequented Romney Marsh in Kent, and in the first quarter of the present century they bred in various suitable spots in Suffolk and Norfolk—the last place known to have been inhabited being Salthouse, where the people made pudding of their eggs, while the birds were killed for the sake of their feathers, which were used in making artificial flies for fishing. The extirpation of this settlement took place between 1822 and 1825. There is some evidence of their having bred so recently as about 1840 at the mouth of the Trent.’ —Newton’s Dictionary of Birds.”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend