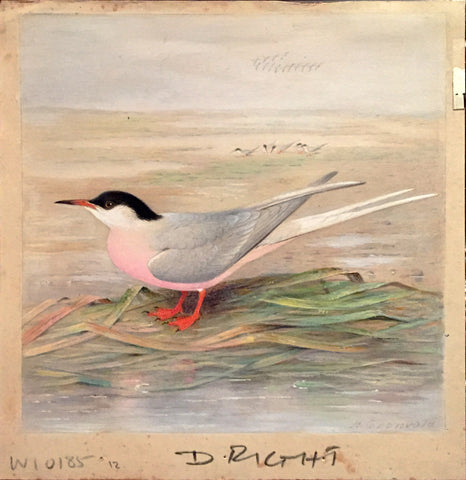

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Sterna Dougalli (Roseate Tern)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Sterna Dougalli (Roseate Tern)”

Prepared for Plate XX W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.r.

1922-1923

Paper size: 6 1/2 x 6 1/2 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“The Roseate Tern was first observed breeding on the small Cumbrae Islands in the Firth of Clyde about the end of the eighteenth century or beginning of the nineteenth, by a Dr. MacDougall of Glasgow; and it was first described in the Supplement of Montagu’s Ornithological Dictionary (1812). MacDougall, writes Seebohm, ‘found several of these beautiful birds in company with great numbers of the Common Tern and sent a skin and many interesting particulars respecting the peculiarities and habits of the new species to Colonel Montagu.” It was then found to be breeding in many places on the Scotch, Irish and English coasts, also the Scillies. From that time onwards (attention having been called to it), its diminution began and continued down to the eighties of last century, when it was pronounced extinct as a British breeding species. ‘It is doubtful,’ wrote Seebohm in 1884, ‘whether the Roseate Tern breeds in any part of the British Islands at the present time,’ though the bird had appeared on the Fames and on the Norfolk coast as recently as 1880. In more recent years one of its old breeding-places on the Lancashire coast has been re-colonised, and there are one or two other small colonies which are maintained by means of special protection. Here the birds will linger until all have been obtained by the collectors, or until—until.

The Roseate Tern is at once the most beautiful and the most swallow-like of these swallows of the sea, the breast being tinged with a very soft rosy flush—though this faint exquisite hue is seen only with the binoculars or when very near at hand—and the streamers of the tail being very long, some inches longer than the central feathers. The wings are somewhat shorter and narrower than those of the Common or Arctic Tern, but the flight is even more buoyant and graceful. Howard Saunders says that it is “ more intolerant of interference ” than other Terns; hence many of its old breeding stations have been abandoned owing to egg-collecting. He also attributes the decrease of the species, on the authority of a French naturalist, to the increase of the larger strong-billed Common Tern; but there is little need to cast about for any such explanation. The two birds had probably nested on the same ground, or in close neighbourhood, for many years before Montagu’s time, though it is unlikely that their numbers were ever great. Mr. Bickerton who, in The Home Life of the Terns , describes a breeding site and the behaviour of the birds, tells us that he found them preferring to associate themselves with the Common Tern rather than with the Arctic, though also preferring to nest in solitary pairs and nearer to the edge of the cliff than the ground selected by their relations. They were, he points out, never numerous, because the British shore is on the further northern fringe of their breeding range; therefore comparatively few reach our islands on the annual migration. When Mr. Bickerton came to exhibit his lantern slides of the bird at a meeting of the British Ornithological Club in 1909, Mr. W. R. Ogilvie-Grant wrote: ‘I hope you will not give the locality of the Roseate Terns, as once the spot is generally known it will be hard to keep exterminators off.’ Since such localities have been known, whether on the Cum-braes or Fames, or the Scillies, or in Ireland, it has been indeed not hard, but impossible, to keep exterminators off.

Some few years ago a well-known private collector offered a couple of the eggs, or a couple of clutches of eggs, to the British Museum (Natural History) as a joint gift from himself and the owner of the place where they were taken. It was a piece of unexampled generosity no doubt. But it turned out that these eggs had been illegally taken, since they were protected by the law, that a watcher was employed to guard them, that the visitor, though citing the landowner’s name, was unknown to him and had been warned not to take the eggs, and that the landowner knew nothing about the whole business, from nesting-ground to museum, until after the event.

‘Formerly a tolerably common summer visitor to several localities in our Islands, has become of late years a decidedly rare British bird.’— Lilford’s Birds of the British Islands.

‘This very elegant Tern was first discovered by Dr. Macdougall, after whom it was named, on an island called Cumbray in the Firth of Clyde. It has since been observed in divers other localities, among them in Cumberland, at Brugh Marsh Point, on the Solway Firth. They breed on the Fern Islands, the Walmseys, and Coquet Island, off the Northumbrian land, also in numbers on Foulney Island, on the coast of Lancashire, and at Scilly; in Scotland in the Isle of May, in the Firth of Forth, and, as already mentioned, in the Cumbray Islands.’ —Morris’s

British Birds.

‘In 1896 Dr, Sharpe was informed of another “ nice little colony ” established in Wales, so that reasonable hope may be entertained of the beautiful Roseate Tern thoroughly re-establishing itself in our Islands after being apparently on the very brink of extinction. Great care, however, will be necessary, and the few resorts of this species kept as secret as possible, and free from the intrusion of trading and grabbing collectors.’— Dixon’s Lost and Vanishing Birds.

‘The Roseate Tern was nesting in fair numbers in Scilly up to the early forties, but only a few pair were there in 1854, and it was last seen about 1867.’—H. W. Robinson, British Birds, XIV. 65 (1920).

‘The Roseate Tern is not only by far the rarest of our British nesting species of Tern, but it is also [one of] the rarest of British breeding birds. . . . Being so rare it is the more worthy of all the protection that bird-lovers can extend to it.’—W. Bickerton, Home Life of the Terns (1912).”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend