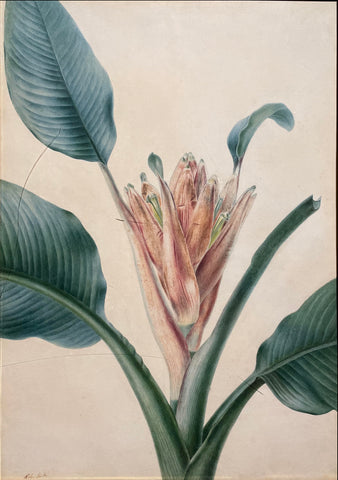

Chinese Export (late eighteenth-century), Pineapple (Ananas camosus)

Chinese Export (late eighteenth-century)

Pineapple (Ananas camosus)

Gouache on paper

Paper size: 18 1/4 x 14 in

Frame size: 27 1/4 x 23 3/8 in

1790-1810

Provenance: Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Verner Reed, Greenwich, CT; and thence by descent to Mr. Samuel P. Reed, New York, NY.

Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) wrote of the pineapple:

“This Fruit is planted and us'd by way of des[s]ert (having a very fine flavour and tast[e]) all over the hot West-Indies, either raw or, when not yet ripe, candied, and is accounted the most delicious Fruit these places, or the World affords, having the flavour of Raspberries, Strawberries, etc., but they seem to me not to be so extremely pleasant, but too [sour], setting the Teeth on edge very speedily [...] It is clear'd of its outward Skin when ripe, and cut into slices, and so eaten, the middle fibrous or woody part being thrown away. It is known when ripe by the colour of the tuft of Leaves at top, which then turn yellow, and will easily come off with the least pulling. This Tuft as well as young Spouts or Succors from the old ones sides, are planted in any hot Soil, and seldom miss to prosper. The slices are soaked in Canary [a fortified wine] to take of the sharpness which commonly otherwise inflames the Throat, and then they are eaten.” (Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers, and Jamaica, 2 vols (London, 1707-25), I, p. 191.)

Although whole pineapple plants could be exported to America and Europe by sea, the fresh fruit itself was commonly candied before transit as it was too perishable to survive the long trip. In England, the first pineapple was grown at Dorney Court, Dorney in Buckinghamshire, and a huge "pineapple stove" to heat the plants was built at the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1723. Because of the expense of direct import and the enormous cost in equipment and labor required to grow them in a temperate climate, using hothouses called "pineries", pineapples soon became a symbol of wealth.

CHINESE EXPORT (LATE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY)

This is an outstanding collection of Chinese export watercolors, illustrating lush and exotic fruits found throughout the Asian continent. One of the leading experts on the arts of the China Trade, Carl L. Crossman, has confirmed their authenticity and describes them as “wonderful examples” of early Chinese watercolors made for export. The identification of each fruit has been confirmed by Dorrie Rosen and Marie Long of the New York Botanical Garden.

The market for Chinese export watercolors grew out of the trade-in porcelain to the West. In Britain, botanical interest in the exotic botany of the world was spurred on by Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), the president of the Royal Society. However, the botanical treasures of China must have been known in England well before 1750, since Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) owned a fine album of such drawings, now in the British Museum. There was a long tradition of botanical writing and illustration in China, dating back to the Song dynasty (960-1279), and the desire of Western scholars to obtain accurate depictions of unfamiliar Asian flora and fauna was easily satisfied by Chinese natural history watercolorists. The tradition of botanical painting was so prevalent throughout China that western traders were not solely reliant upon the workshops at Canton, the main trading city-port, and also obtained watercolors from other parts of the Chinese community in southeast Asia

These particularly fine examples date from the late eighteenth century and display an acute sense of scientific accuracy balanced by a strong aesthetic sensibility. It is probable that they were originally commissioned by a Western scholar or amateur gentleman-botanist curious as to the appearance of the exotic fruits of Asia. As is typical of Chinese export watercolors of this period, each work shows the fruit with its complete vegetation and also contains a cross-section illustration depicting the interior flesh of the fruit. Each of these minutely detailed, exquisitely colored, and fully animated renderings seem ready to burst out of its compositional boundaries. Indeed, from the incredibly life-like rendering of a pineapple’s prickly scales to the emotionally charged depictions of seeds liberating themselves from their shells, it is clear that the watercolorist possessed an incredibly heightened scientific and decorative sense.

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend