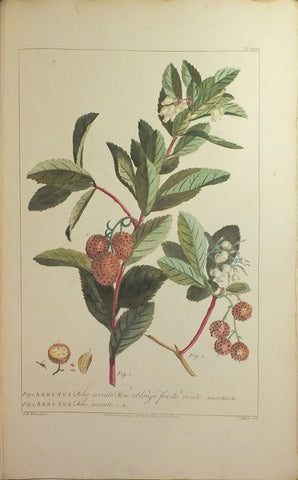

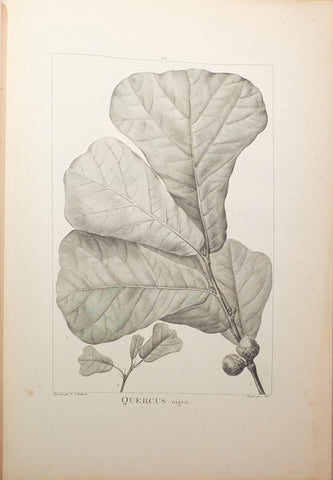

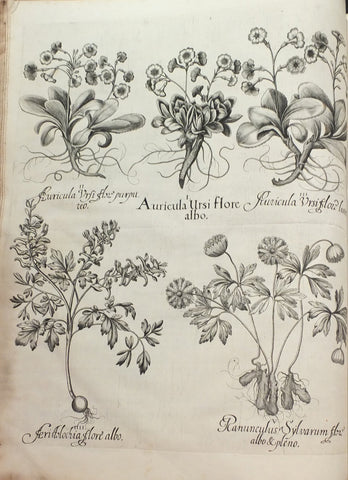

Philip Miller (1691-1771), Figures of the most Beautiful, Useful, and Uncommon Plants described in The Gardeners' Dictionary...

Philip Miller (1691-1771)

Figures of the most Beautiful, Useful, and Uncommon Plants described in The Gardeners' Dictionary...Their Descriptions, and an Account of the Classes to which they belong.

London: printed for the Author, [1755-] 1760

2 volumes. Folio (17 2/8 x 11 inches). Engraved vignette on dedication leaf, 300 fine hand-colored engraved plates (including two folding with small closed tears near the gutter), many printed in green or sepia, Thomas Jefferys, and J. Mynde, after Georg Ehret (16), Johann S. Müller, Richard Lancake, J. Bartram, and W. Houston, woodcut headpiece and initial (some minor offsetting). Contemporary half-calf, marbled paper boards (extremities scuffed with some surface-wear).

Provenance: Near contemporary ownership inscription of Ben Palmer on each title-page.

"the most distinguished and influential British gardener of the eighteenth century" (DNB).

First edition, and an attractive and unsophisticated copy, originally published in 50 parts of 6 plates each. Although Miller's plan had originally been to "exhibit the Figures of One or more Species of all the known Genera of Plants", he had ultimately been obliged by the expenses of production to "contract his Plan, and confine it to those Plants only, which are either curious in themselves, or may be useful in Trades, Medicine, &c., including the Figures of such new Plants as have not been noticed by any former Botanists" (Preface). Preceded by his celebrated "The Gardeners Dictionary" (which ran to eight editions (1732-1768) during Miller's lifetime his works were commended at the time for being "drawn from nature in the best state of flowering, and for including illustrations of fruit and seed as they ripened" (DNB). In 1722 Miller was appointed by Hans Sloane and the Society of Apothecaries as gardener for their Physic Garden at Chelsea. A condition of Sloane's deed of conveyance of the garden to the apothecaries was that they present annually to the Royal Society fifty dried specimens grown in the garden in the previous year. This necessitated the continuous introduction of new plants, achieved only by Miller's wide correspondence: "from various parts of the world. Exchange with John Bartram of Philadelphia, a collector of plants in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Delaware, and elsewhere, was particularly fruitful. Kalm [a student of Linneaus at Uppsala] observed that 'the principal people in the land set a particular value on this man' (Kalm, 111). The fourth duke of Bedford [to whom this volume is dedicated] employed him on a regular basis to visit Woburn and inspect gardens and hothouses and to prune the trees. These included many American conifers, and Miller approved introductions of alternative timber owing to the great quantity of oak needed by the Royal Navy. He also catalogued numerous American plants grown by the young Lord Petre at Thorndon, Essex. His advice was sought by the dukes of Richmond at Goodwood, where his suggestions for a flower border remain. The Society of Arts consulted Miller on agricultural matters, from winter feed for domestic animals in England to grapes suitable for the climate of South Carolina. On the latter Miller often consulted growers in both France and Italy, and he was a member of the Botanic Academy of Florence; from both countries he received seeds" (DNB). Like his father before him Ehret trained as a gardener, initially working on estates of German nobility, and painting flowers only occasionally, another skill taught him by his father, who was a good draughtsman. Ehret’s “first major sale of flower paintings came through Dr Christoph Joseph Trew, eminent physician and botanist of Nuremberg, who recognized his exceptional talent and became both patron and lifelong friend. Ehret sent him large batches of watercolours on the fine-quality paper Trew provided. In 1733 Trew taught Ehret the botanical importance of floral sexual organs and advised that he should show them in detail in his paintings. Many Ehret watercolours were engraved in Trew's works, such as ‘Hortus Nitidissimus’ (1750–86) and ‘Plantae selecta’e (1750–73), in part two of which (1751) Trew named the genus Ehretia after him. “During 1734 Ehret travelled in Switzerland and France, working as a gardener and selling his paintings. While at the Jardin des Plantes, Paris, he learned to use body-colour on vellum, thereafter his preferred medium. In 1735 he travelled to England with letters of introduction to patrons including Sir Hans Sloane and Philip Miller, curator of the Chelsea Physic Garden. In the spring of 1736 Ehret spent three months in the Netherlands. At the garden of rare plants of George Clifford, banker and director of the Dutch East India Company, he met the great Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, who was then formulating his new classification based on plant sexual organs. Ehret painted a Tabella (1736), illustrating the system, and sold engravings of it to botanists in Holland. Some of his paintings of the exotics were engraved in Linnaeus's “Hortus Cliffortianus” (1737). “[Ehret] signed and dated his work, naming the subject in pre-Linnaean terms. He published a florilegium, “Plantae et papiliones rariores” (1748–62), with eighteen hand-coloured plates, drawn and engraved by himself... Ehret also provided plant illustrations for several travel books. His distinctive style greatly influenced his successors” (Enid Slatter for DNB). Two plates in the "Figures of the Most Beautiful." are of Mexican and West Indian plants collected by the plant collector William Houston. Dunthorne 209; Great Flower Books, p. 68; Henrey 1097; Hunt 566; Nissen 1378; Stafleu & Cowan TL2 6059.

We Also Recommend