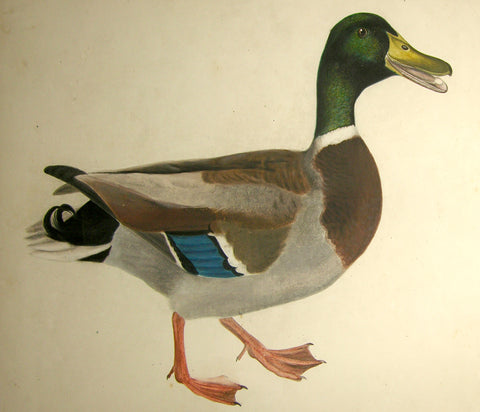

Prideaux John Selby (British, 1788-1867), “Common Wild Duck” (Mallard Duck)

Prideaux John Selby (British, 1788-1867)

“Common Wild Duck” (Mallard Duck)

Original watercolor prepared for Plate 50 of Illustrations of British Ornithology

Watercolor, gouache, grey and brown washes on paper

Signed lower left: PJSelby

London, ca. 1820

Paper size: 19 x 15 1/2 in

Frame size: 31 1/4 x 28 in

“Amongst the various species of the present beautiful subfamily of the Anatidce, few display a more chaste and delicately pencilled plumage than the Mallard in his matured state. This, however, is very apt to escape the degree of attention it deserves, from our becoming so much accustomed to the appearance of his domesticated brethren; who, though frequently retaining all the colours and distinctive markings of the original stock, cannot, with their dull and heavy appearance, compensate for the sprightly look and graceful form that will strike the closer observer as distinctive of this bird in a state of nature. This is an indigenous species, and, although banished by the advance of agriculture from vast tracts of country that formerly provided it with suitable breeding retreats, still inhabits the shores of our lakes and rivers, with such upland boggy grounds as have not yet been submitted to the system of drainage that has of late years so altered the face of the country. These changes in the character of the soil, have of course produced a great, and, I may add, annual decrease of our native breed, which must progressively happen as long as the causes producing it are in operation. It is probable, therefore, that in a few years the Common Wild Duck will become comparatively rare as an indigenous species, except in some few localities that may bid defiance to agricultural improvement. In such case, the deficiency will, during the winter months, be supplied in part by additional arrivals from the more northern countries, to which this bird will naturally resort for the purpose of reproduction, under more favourable auspices The estimation in which the flesh of the Wild Duck, both for delicacy and flavour, has ever been held at the table, has caused various devices to be resorted to for its capture, of which none appear to be so effectual as the decoy. It is by this method that the greatest part of the birds annually sent to the London market are taken, and its practice is allowed from October till February. In ten of these decoys in the neighbourhood of Wainfleet, it is recorded that 31,200 wild fowl were taken in one season, of which more than two-thirds were of the present species. WILSON, in his North American Ornithology, has described several other modes of taking these birds that are in use in that country, and mentions also that singular and ingenious method adopted in India and China, where the sportsman, covering his head with a calabash or wooden vessel, wades into the water, and, keeping only his head thus masked above it, advances towards and mixes with the flock, who feel no alarm at what they look upon to be a mere floating calabash. He is thus enabled to select his victims, whom he seizes by the legs, and pulling them under water, fastens them to a girdle with which he is equipped, thus carrying off as many as he can stow away, without exciting distrust and alarm amongst the survivors. The Wild Duck is widely distributed through most of the temperate and arctic regions of the globe ; in the former of which it is only a winter visitant, as the great body of these birds retire even beyond our parallel of latitude for the purposes of reproduction. In all the countries where it has been met with, its qualities for domestication seem to have been recognised and turned to advantage ; and, though from long continuance of the breed in a state of confinement, great variety in colour, size, &c. has been produced, the male bird constantly retains the peculiar specific distinction of the curled feathers of the tail. In China and other eastern countries, great numbers of ducks are hatched by artificial means, by the eggs being placed in tiers in boxes filled with sand, and subjected to the necessary degree of heat, upon a floor of bricks. The ducklings are fed at first with a mess composed of boiled craw-fish, or crabs, cut in small pieces, and mixed with rice. In about a fortnight they are able to shift for themselves, when they are placed under the guidance of an old stepmother, who leads them at stated times to feed, to and from the sampane (or boat) in which they are kept, and which is moved about by the owner to places likely to afford a plentiful supply of food. In a natural state. Wild Ducks always pair, though in a state of domestication they are observed to be polygamous. This pairing takes place towards the end of February or beginning of March, and they continue associated till the female begins to sit, when the male deserts her, joining others of his own sex similarly situated ; so that it is usual to see the Mallards, after May, in small flocks by themselves. About this time also they begin to undergo the changes of colour that assimilate them in a great degree to the female, and which is retained till the period of the autumnal or general moult. The care of the young thus devolves entirely upon the Duck, and is not partaken by the male, as WILSON and others appear to think ; and this fact I have had frequent opportunities of verifying, as many Wild Ducks annually breed upon the edges of our Northumbrian moors, and the young broods are of course frequently under inspection as they descend the rivulets to the lower Nest, &c. marshy parts of the country, The nest of the Wild Duck is generally made in some dry spot of the marshes, and not far from water, to which she can lead her progeny as soon as hatched. It is composed of withered grass, and other dry vegetable matter, and usually concealed from view by a thick bush, or some very rank herbage; though other and very dissimilar situations are occasionally chosen, as several instances have been recorded where they have deposited their eggs on the fork of a large tree, or in some deserted nest. Such an instance once occurred within my knowledge, and near my own residence, where a Wild Duck laid her eggs in the old nest of a crow, at least thirty feet from the ground. At this elevation she hatched her young ; and, as none of them were found dead beneath the tree, it is presumed she carried them safely to the ground in her bill, a mode of conveyance known to be frequently adopted by the Eider Duck. When disturbed with her young brood, the Wild Duck has recourse to various devices to draw on herself the attention of the intruder, such as counterfeiting lameness, &c. which manoeuvres are generally successful; and in the mean time the young ones either dive or secrete themselves in the bushes or long herbage, so that it rarely happens that more than two or three are captured out of a large brood. The eggs are from ten to fourteen, of a bluish-white; and the Duck, during incubation, when she quits the nest for food, is in the habit of covering them with down and other substances, in all probability from an instinctive idea of concealing them from observation, and which ‘practice is pursued by many birds as well of this as other families. The trachea of the Mallard is furnished at its lower extremity with a labyrinth (not unlike that of the Gadwall in shape and position, but considerably larger), yet the tube itself is of nearly equal diameter throughout its length. The Food, food of the Wild Duck consists of insects, worms, slugs, and all kinds of grain, &c.

PLATE 50. Represents the Mallard, of the natural size. Head and neck glossy duck-green, with the lower part General surrounded by a narrow collar of white. Breast deep chocolate-red. Under parts greyish- white, with fine Male, zigzag transverse lines of grey. Mantle chestnut-brown, with the margins of the feathers paler. Scapulars greyish-white, rayed with zigzag brown, those next to the wing being rich brown, rayed with black. Lower part of the back, rump, and under tail-coverts velvet-black, with green reflections. The four middle tail-feathers black, and curled upwards ; the rest hair-brown, deeply margined with white. Lesser wing-coverts hair-brown, tinged with yellowish-brown. Greater coverts having a bar of white, and being tipped with velvet-black. Speculum rich glossy Prussian blue, passing into black, and tipped with white. Quills pale hair-brown. Bill honey-yellow, with a greenish tinge. Legs and toes orange.

PLATE 50. The Female, also of the natural size. Female. Head and neck dirty cream-yellow, with numerous streaks of brown, which are darkest upon the crown. Chin and throat pale buff. Upper parts umber-brown, of different shades, with the feathers margined with cream- coloured white. Lesser wing-coverts pale hair-brown, tinged with grey. Speculum purplish-blue, passing in- to velvet-black, with the tips of the feathers white. Quills pale hair-brown. Breast and under parts yellowish-brown, spotted and streaked with darker brown. Legs orange. The young males resemble the females till after the autumnal moult.”

Considered by many as the English equivalent of Audubon, Prideaux John Selby created some of the most memorable bird images of the nineteenth-century. His contributions to British ornithology were rivaled only by those of John Gould. Yet, his pictures were larger and less purely scientific, exhibiting Selby’s distinctive and charming style. A sense of Selby’s enthusiasm for his subjects is nowhere more palpable than in his engaging original watercolors. Selby executed these delightful images as preparatory models for his landmark printed series, Illustrations of British Ornithology. While the artist’s engraved work is highly desirable to collectors, Selby’s original watercolors rarely become available. This selection of watercolors, moreover, comprises several of his masterpieces. The distinctive birds are depicted in profile, their forms delineated by softly modulated tones of black and gray wash. The setting, if present, is lightly but skillfully painted to not distract from the birds themselves. The skill and delicacy of Selby’s touch, his keen powers of observation, and his artistic sensitivity are conveyed here in a way they are not in his printed work. Several of the drawings are by Selby’s brother-in-law, Robert Mitford, but signed in Selby’s hand.

Born in Northumberland and educated at University College, Oxford, Selby was a landowner and squire with ample time to devote to studying the plant and animal life at his country estate, Twizell House. As a boy, he had studied the habits of local birds, drawn them, and learned how to preserve and set up specimens. Later, Selby became an active member of several British natural history societies and contributed many articles to their journals. Although Selby was interested in botany and produced a History of British Trees in 1842, he is best known for his Illustrations of British Ornithology. Selby’s work was the first attempt to create a set of life-sized illustrations of British birds, remarkable for their naturalism and the delicacy of their execution. The British Ornithology was issued in nineteen parts over thirteen years; the book consisted of 89 plates of land birds and 129 plates of water birds, engraved by William Lizars of Edinburgh, the printer who engraved the first ten plates of Audubon’s Birds of America.

With their rich detail and tonal range, these exquisite watercolors are beautiful works by one of the foremost British bird painters. Furthermore, they represent a singular opportunity to obtain a unique piece of the highest quality by this luminary artist, from an era in British ornithological art that remains unparalleled.

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend