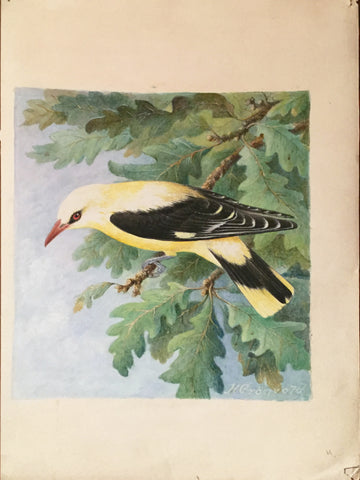

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Oriolus Galbula (Golden Oriole)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Oriolus Galbula (Golden Oriole)”

Prepared for Plate XXIII W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.r.

1922-1923

Paper size: 8 1/2 x 6 1/8 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“Doubtless the Golden Oriole is one of the migratory-species that do not remain, young and adult, everlastingly in the same limited area, or neighbourhood, but fly forth to explore new ground, and if they find a suitable spot they colonise. Thus, although the bird is decreasing with us we still have it as a recurring visitant to these islands: where it is collected as soon as seen. Why collected ? may well be asked, seeing that its rare and brilliant colouring—the daring of its pied black and golden-yellow—would cause it to shine among the somewhat soberly clad species of our woodlands like a gleaming topaz in a necklace of little brown and green and freckled stones. The answer is, because a British-killed specimen is worth much more to the basest of all collectors, he who looks to make something by killing a visitor to our shores, than he would get by a specimen of the same species from France or elsewhere in Europe. And yet he knows, and the man who buys it from him knows, that the British-killed specimen is a French, or Belgian, or Dutch bird, and not British; also that it is through him and others of his kind, that we have no British Orioles.

Sometimes the Golden Orioles arrive in numbers, as was the case in May 1870, when forty were seen in one flock. This was close to the town of Penzance, where I am now writing. I have talked with the old head-keeper of the woods in which they appeared. Everyone in the place was up and after them, and soon they were all shot, he told me.

Another county where they would, undoubtedly, nest if allowed to do so, and where they have bred not only once but with a determination only overcome by the greater determination of the collector to prevent their doing so, is Kent. Apart from actual nesting records, Mr. N. F. Ticehurst compiled a list of sixty-five instances of Golden Orioles being either seen or shot (usually both) in that county since 1834, ‘an d there are very few years unrepresented in the list, while only four apply to any other season than spring.’ I may here quote briefly from the History of the Birds of Kent , which I also quoted in writing of the Kentish Plover. Before 1834 Orioles had been noticed as visitors to the county, and in that year several were shot near Sandwich. Two years later a nest was found, and the young birds were taken; and a useless attempt was made to rear them in captivity. When again a nest was discovered, the young were taken, this time by a countryman to feed his ferrets. Between 1840 and 1845 further birds were seen and shot. In 1849 a nest was found at Elmstone; the birds were shot and the nest and eggs taken by a parson of the neighbourhood. Next year a female bird was shot in the same place. In another parish a second pair nested; the nest and eggs were taken and ‘long carefully preserved at the rectory there.’ Four more Orioles, obtained at Elmstone, are ‘carefully preserved’ in a private collection. So the miserable story goes on.

In a certain park in Thanet a pair were shot in 1874, but the owner of the place, strangely enough, gave orders that if any more appeared they were not to be killed. Consequently the birds nested there safely until 1883. In that year two eggs were taken, the park changed hands, and the next arrivals were promptly shot. The birds have made no further attempt to nest in that park.

Early ornithologists confused the Golden Oriole with the Green Woodpecker. This is somewhat singular, seeing that both birds are of uncommon and showy plumage, but yellow is the colour most conspicuous in both when flying. Turner supposed he might identify Aris to tie’s Vireo or Witwel, ‘of a dusky green colour,’ with the bird that suspended its nest ‘upon a branch at the top of a tree that it should not afford access to any man or beast.’ The ‘Galgulus,’ which ‘is yellowish in colour and hacks the timber very much’ he thought to be the Huhol of the English. Hewhole, or Hewel, and Witwall or Withol, are old English names for the Woodpecker. Marvel wrote: ‘But most the Hewel’s wonders are, Who here has the holtfelster’s care; He walks still upright from the root, Meas’ring the timber with his foot.’

The Percy Ballads have ‘the wood weele sang,’ which is explained in Walford’s Glossary to mean a Golden Owl, a bird of the Thrush kind, and by others has been imagined to refer to the Woodpecker. More probably it is intended for the Oriole, since the poet says that ‘it sang and would not cease, sitting upon the spraye.’ Our old naturalist Willughby, describing the Oriole, says: ‘All the body is of a bright yellow, very beautiful to behold: so that for the lustre and elegancy of its colours it scarce gives place to any of the American birds. . . . The Low Dutch call this bird by a very fit name, Goutmerle, that is, Golden Ouzel, for it agrees with Thrushes or Blackbirds in the shape of the bill and the whole body; in the bigness, also food, and manner of living. It is called Galbula or Galgulus from its yellow colour.’

Our later writers have little to say about the bird, save that it might and would breed, but is not allowed to do so. We may turn to letters written during the great war by some of our men who were in France, to know what impression it conveys in a country where it is abundant. Thus, one wrote in the Times (May 1916): ‘The Orioles are, of course, the chief joy of the wood. They are always in the same small section. One has only to go there and stand still for awhile and sooner or later the beautiful flute-like liquid call comes ringing from somewhere out of the green world above. Then a brilliant meteor of yellow and black flashes through a gap between the tree-tops, and the liquid note which sounded on the right hand is now on the left. Then it is behind one, then in front. And another says: ‘Orioles are amusing, active birds, full of life and sound.’ In England they are in the collectors’ cabinets, full only of dusty death.

‘Ordinary readers are scarcely aware how frequently this handsome and conspicuous bird visits the British Isles or that it has actually bred in them. So far as we can see, there is nothing to prevent the Golden Oriole becoming as common on this side the English Channel (as it most probably was in remoter ages) as it is on the other side. The bird is said to be a regular spring visitor to the Scilly Isles and Cornwall, and thence onwards through the Southern Counties as far as Norfolk, but with perhaps less frequency. It must be remembered that such very showy birds have difficulty in penetrating far after once landing on such inhospitable shores as ours.’—C. Dixon, Lost and Vanishing Birds.

‘I cannot too emphatically impress upon my readers that these birds arrive in spring in pairs with the fixed intention of nesting, and that, with the exception of Cornwall and the Scillies, Kent is the only county where they do so with any approach to regularity, so that no one with any love for our country’s birds ought to do otherwise than protect them to the utmost of their ability.’— Ticehurst’s Birds of Kent.”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend