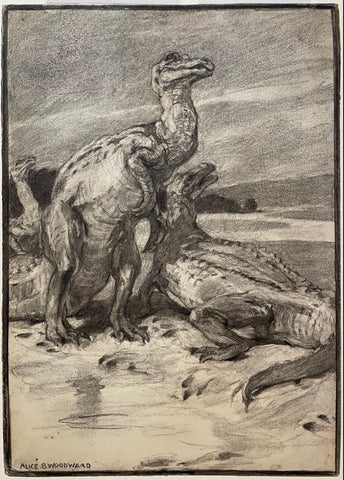

Alice B. Woodward (British, 1862-1951), Iguanodonts Remains found in England and Belgium

Alice B. Woodward (British, 1862-1951)

“Iguanodonts Remains found in England and Belgium”

Preparatory drawing for “Iguanodonts” in Evolution in the Past page 98

Charcoal pencil on paper-faced pasteboard

Signed ‘Alice B. Woodward’ lower left

Board size: 10 3/4 x 7 1/2 in.

Iguanodontians were one of the first groups of dinosaurs ever to be found. They are among the best-known dinosaurs and were among the most diverse and widespread herbivorous dinosaur groups of the Cretaceous period. Many early Iguanodonts had long arms and were partly quadrupedal: the feet of Tenontosaurus and Camptosaurus were four-toed, while those of Dryosaurus had three weight-bearing toes, as was the case with more derived iguanodonts. The tails of iguanodonts also evolved into a deep, stiff counterbalance that probably assisted the animals in bipedal movement.

What is often left out of this discovery is one of the fossilist: Mary Ann Mantell (née Woodhouse 1795-1869). It is widely recorded that in 1822, Gideon Mantell (1790-1852) and his wife, Mary Ann, visited a patient near Lewes in the English countryside, and Mary Ann “stumbled upon a few fossils while walking through the countryside.” The story purports “together,” the couple studied the fossils and recognized that the remains were from a large animal with reptilian features. Gideon’s resulting publication of their findings was the first to correctly describe such fossils as those of a large, unique reptilian creature that had become extinct. Nineteen years before the term dinosaur was popularized in scientific literature. In 1825, Mantell published a subsequent paper naming their fossils as part of an Iguanodon (“iguana tooth” ): the first dinosaur described as an ornithopod.

Per the Mantells’ account, Mary Ann discovered a collection of fairly large teeth embedded in the rocks which were later identified as belonging to Iguanodon. Her husband Gideon, also an amateur palaeontologist, showed the teeth to Charles Lyell who brought them to Georges Cuvier, who initially told Lyell he thought the teeth were from a rhinoceros; he retracted that statement the very next day but all Lyell reported to the Mantells was Cuvier’s initial dismissal of the discovery: the teeth were thought to be from a rhino.

Another naturalist William Buckland, was shown the teeth and felt they were something else entirely. The Mantells approached Cuvier again, and Gideon’s “discovery” and Cuvier’s response to the Mantells was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1825. Cuvier stated, “These teeth are certainly unknown to me; they are not [from] a carnivorous animal, and yet I believe that they belong, given their little complication, their serrating on the edges, and the thin layer of enamel that revet them, to the order of the reptiles. The outside appearance could also be taken for fish teeth similar to tetrodons, or diodons; but their internal structure is very different from those of [that type]. Wouldn’t we have a new animal here, a herbivorous reptile?” Cuvier’s statement “these teeth are certainly unknown to me,” makes it clear he had either never seen the fossilized teeth, leading one to question, was he shown them intially? Or was it an attempt to repackage the discovery with a preferred scientific figure out front? Gideon Mantell “at first endorsed but recanted” this story after their subsequent divorce. One must question the recantation of this story and its timing. The true story is still debated to this day, and may be romaticized because of its dramatic turn of events. It has been said, Gideon inserted a falsity claiming Mary Ann had not discovered the fossils but bought them from a quarryman rather than admit her discovery.

Mary Ann was not only an early fossil hunter, but she was quite a skilled artist. She provided illustrations for the couple’s discoveries. Gideon did mention her in his subsequent publication, The Fossils of the South Downs (1822). Not by name, of course, instead, he wrote that he “was very proud of his wife’s work.” But, predictably, he could not help himself but point out flaws to denigrate the over 300 illustrations she provided for work presented solely under his name. He followed with, “as the engravings are the first performances of a lady but little skilled in the art, I am most anxious to claim for them every indulgence ... although they may be destitute of that neatness and uniformity, which distinguish the works of the professed artist, they will not, I trust, be found deficient in the more essential requisite of correctness.” It should come as no surprise Mary Ann and Gideon divorced. Gideon later inadvertently exposed the weakness lay in his inability to accept her abilities as a scientist and artist, writing, “There was a time when my poor wife felt deep interest in my pursuits, and was proud of my success, but of late years that

feeling had passed away and she was annoyed rather than gratified by my devotion to science.”

Alice Woodward’s illustration of the “Iguanodonts Remains found in England and Belgium” takes on a fascinating layered nuance when the context is understood. Whether Alice knew of Mary Ann’s contributions is unknown. However, one must ask, was this a mere coincidence? Or were women’s contributions so pervasive that this is a rare example found to date; many more may await our discovery.

ALICE WOODWARD (BRITISH, 1862-1951)

Alice Woodward is perhaps more widely known as a children’s book illustrator, an “acceptable” field for female achievement in her lifetime. Still, she should be known as one of the pioneer artists in paleoart, imagery that depicts what life on Earth might have been like millions of years ago.

Alice was the daughter of Henry Woodward, keeper of the Department of Geology at the British Museum and President of the Paleontographical Society from 1895 to 1921. Henry encouraged all his children to draw. As was the climate of the times, his daughters became artists and his sons became scientists.

Alice prepared illustrations for her father’s lectures and colleagues’ papers by her late teens. Through these associations and her father’s encouragement, she was eventually tapped to produce images for the critical publications Henry Knipe’s Nebula to Man (1905) and Evolution in the Past (1912). Knipe, a colleague of Dr. Woodward, chose each illustrator for their reputation for scientific authenticity— particularly bird artists, given the many similarities between bird species and dinosaurs.

Drawings prepared for Knipe’s publications contributed to one of the most important publications on dinosaurs during what is frequently referred to as the “Second Rush” of the Great Dinosaur Rush or Bone Wars. The first Bone Wars occurred between 1877 and 1892 between Edward Drinker Cope, the Academy of Natural Sciences Philadelphia, and Othniel Charles Marsh, the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale. These early paleontologists fought ruthlessly to pursue dinosaur fossils, a quest that resulted in an extraordinary period of discovery and the eventual financial ruin of both scientists. Their findings resulted in unearthing 136 new dinosaur species, ushering in a new era in paleontological research.

While still not a household name in paleoart, we should continue to delve into the history of Alice Woodward, an interesting artist who took textural descriptions of a species never seen by humankind and developed them into a form. It takes astounding intelligence to create a vision of a species in the setting of a world so foreign to modern man and make it real in a remarkably tangible manner. Knipe acknowledged Alice’s pictures as a document of science in the preface to Evolution in the Past, writing, “I acknowledge with gratitude the valuable expert assistance which Miss Alice B. Woodward provided at the British Museum (Natural History.) Her pictures thus possess a real scientific value in addition to their artistic merit.”

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS PREPARED FOR HENRY KNIPE’S

NEBULA TO MAN (1905) & EVOLUTION IN THE PAST (1911-1912)

An exceedingly rare collection of original watercolors prepared for Henry Knipe’s Nebula to Man (1905) and Evolution in the Past (1911-1912) by naturalist-artists Alice Woodward, Josef Smit, and Charles Whymper.

Drawings prepared for Knipe’s Nebula to Man (1905) contributed to one of the most important publications on dinosaurs on the heels of the Great Dinosaur Rush or Bone Wars. The Bone Wars occurred between 1877 and 1892 between Edward Drinker Cope, the Academy of Natural Sciences Philadelphia, and Othniel Charles Marsh, the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale. These early paleontologists fought ruthlessly to pursue dinosaur fossils, a quest that resulted in an extraordinary period of discovery and the eventual financial ruin of both scientists. Their findings resulted in unearthing 136 new dinosaur species, ushering in a new paleontological research era.

According to Henry Knipe’s obituary, he worked for the British Museum. It was there that he likely met the artists tapped for this project. Knipe chose each illustrator for their reputation for scientific authenticity—namely, those skilled as bird artists, given the many similarities between bird species and dinosaurs.

We Also Recommend

![Albertus Seba (1665-1736) Tab I [Insects]](http://aradergalleries.com/cdn/shop/products/I_large.jpg?v=1635434052)

![Albertus Seba (1665-1736) Tab II [Insects]](http://aradergalleries.com/cdn/shop/products/II_large.jpg?v=1635434726)

![Albertus Seba (1665-1736) Tab III [Insects]](http://aradergalleries.com/cdn/shop/products/III_large.jpg?v=1635434877)

![Albertus Seba (1665-1736) Tab L [Insects]](http://aradergalleries.com/cdn/shop/products/L_b_large.jpg?v=1635435506)

![Albertus Seba (1665-1736) Tab L [Insects]](http://aradergalleries.com/cdn/shop/products/L_large.jpg?v=1635437893)