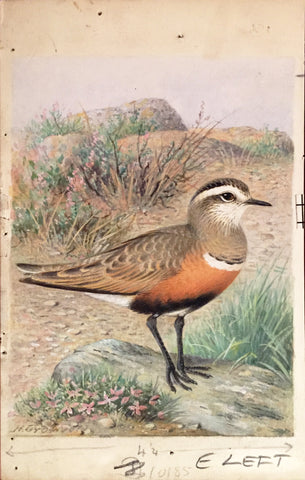

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Endromias Morinellus (Dotterel)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Endromias Morinellus (Dotterel)”

Prepared for Plate XXI W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.l.

1922-1923

Paper size: 9 3/4 x 5 1/2 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“The Dotterel was once very abundant in England, as we may suppose from old records. It is not yet extinct as to the British race, but is one of those species, like the Roseate Tern, which linger on the verge of extinction. It is supposed that four or five or perhaps half a dozen pairs still actually breed in England on the mountains of Westmorland. A considerably larger number inhabit the northern part of Scotland, where they breed on the Grampians and Cairngorms and possibly other heights, at an altitude of 3000 to over 4000 feet—higher in fact than the Ptarmigan, so that during the whole of the breeding season snow lies on the summits where they nest. But even in that wild solitary place above the clouds, where one would suppose their deadliest enemy would be the Golden Eagle or the marauding fox, their chief foe is the egg-seeker for the collectors’ cabinet. For as there are hundreds of private collectors, and every one must have ‘British-taken’ eggs of the Dotterel, there is a very considerable demand; and if this continues, as it must unless prevented by legislation, these lovely little birds will go the way of many others.

The Dotterel has always had to face a various persecution from man. It was coveted as a table bird, and shot on its spring migration, ‘a most unsportsman-like practice’ as one writer thinks it necessary to point out; the feathers were sought to some extent for the making of fishermen’s flies: and when the birds grew too scarce to be worth the sportsman’s attention or to yield a paying quantity of feathers, the collector stepped in to finish the tale. Old writers allude to it as a delicate bird to eat, ‘a daintie dish,’ as Drayton wrote, and we come across mention of it in a household book of the Dukes of Northumberland, 1512: ‘Dotterels to be bought for my Lord.’ It was also early famed for its supposed foolishness; being simple and unsuspicious and therefore easily caught, it was naturally regarded as stupid. Legends grew up as to the manner in which it was imagined the bird would imitate the movements of its would-be captors and walk straight into the net. Dr. Key, or Caius, in a letter to Gesner, relates the fable. ‘It is,’ he says, ‘a very foolish bird, but delicate to eat, and is accounted a great delicacy. It is a mimic, and so, as the Scops and Otis are taken by an imitation of dancing, this bird is caught at night by the light of a candle according to the motion of the captor, for if he stretches out an arm that also stretches out a wing; if a foot that likewise a foot. In brief, whatever the fowler doth, the same doth the bird, and so being intent on men’s gestures it is fooled and caught in the net. . . . Our people call it Doterell, ‘as if they were to say doating with folly.’ Drayton writes: ‘As you creep or cower or lie or stoop or go, So marking you with care the apish bird doth do.’

The simple ground for all this fabrication, which was credited by our ornithologists for the space of two or three centuries, was the one fact that, like many other birds, the Dotterel stretches out a wing and leg when disturbed from its repose. The only folly that the bird is guilty of, Seebohm comments, is that of permitting the near approach of man. But foolishness continues to be its accepted characteristic. Mr. T. A. Coward tells us that when the little parties, or ‘trips’ arrive in England in spring, on their way to their breeding-quarters, they are tired and stupid, and if fired at will settle again at once: ‘it was not uncommon for the whole trip to be wiped out: within recent years similar massacres having come to my notice.’ We are reminded here of Lord Lilford’s description of the actions of the Kentish Plover, the Dotterel’s near relation, as he observed it in Spain. ‘If a flock be fired at many of the survivors will very soon return to the spot from which they were startled.’

‘These birds are getting more and more scarce in the neighbourhood of the Lakes; and from the number that are annually killed by the anglers of Keswick and its vicinity—their feathers having long been held in esteem for dressing flies—it is extremely probable that in a few years they will become so extremely rare that specimens will be procured with considerable difficulty.’ So wrote Mr. T. C. Heysham in 1834— an ardent collector who killed as many Dotterels, old and young, and took as many eggs as he could find. Naturally he cursed the anglers.

Morris says that formerly numbers could be obtained on the Yorkshire wolds when the birds were on their way back to the mountains in the north-west, but that in his time one had to be up early in the morning and range the country on horseback before the ploughman was up, to obtain even a few. They were then to be found breeding, however, in the Lake district, in Westmorland and Cumberland, on Robinson Fell, Great Gable, Whiteside, Helvellyn, Saddleback, Watson Dod, Great Dod, and Skiddaw, also in Northumberland. ... ‘In Scotland they breed about Braemar, also on the Grampian hills, and in Elgin, Dumfriesshire, Sutherland, East Lothian, the Lammermoor hills, and other parts.’ They are said to have been seen in spring in comparatively recent times on the Merioneth mountains, and even on Salisbury Plain, both perhaps memories of old-time breeding grounds.

‘The Dotterel probably bred years ago on some of the wildest hills in the south of England, but it has long since ceased to do so, having been exterminated by collectors and others. Even whilst on migration it is subject to incessant persecution, and naturally retires to those few chosen habitats in the wildest parts of Scotland where it can rear its young unmolested by man.’— Seebohm’s British Birds.

‘In spite of centuries of persecution it still nests in small numbers in the Lake District and in the Grampians and other Highland mountains, but in most parts is only known as a scarce spring visitor. Towards the end of April or early in May ‘trips,’ as the small parties are called, arrive in England, and their arrival is, or was, watched for keenly, for the Dotterel has always had a high money value, originally for its flesh, but later for its plumage; inconsiderate fishermen demand certain feathers for artificial flies. . . . Egg collection is responsible for further diminution in numbers, but is less to blame than the wholesale destruction of recently arrived immigrants.’— Coward’s Birds of the British Isles.”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend