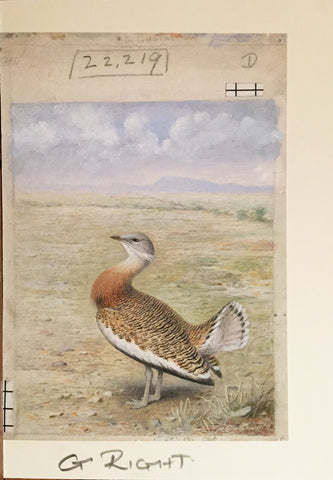

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Otis Tarda (Great Bustard)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Otis Tarda (Great Bustard)”

Prepared for Plate VI W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on card

1922-1923

Board size: 10 1/8 x 6 1/2 in.

Paper size: 8 5/8 x 5 1/2 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“The Great Bustard is the largest of all the birds ever recorded as residents of Great Britain. Its wing measurement is seven to eight feet, and the male weighs as much as thirty pounds. The first mention of it as an inhabitant of this country occurs in the History of Scotia by Hector Boethius (1526), where it is called the Gustard and is said to breed in the lowlands of Merse in Berwickshire. It was last shot in Scotland in 1830. Other early references are mainly to its use for the table, as in the Earl of Northumberland’s regulations for his household at Wressil and Lekinfield in Yorkshire, where they are ordered to be dished ‘for my Lordes owne Mees at Pryncipall Feestes;’ and in the Household Books of the L’Estranges of Hunstanton, where there is an item of ‘viij malards a bustard and j heresewe kylled w* ye crosbowe.’

About the best history we have of the Great Bustard, as a British species, is contained in Stevenson’s Birds of Norfolk, and occupies the first forty pages of the second volume of that excellent work. Of the Bustard itself not much is to be learnt from this, or from any other book on British birds. Strange to say, that when this grand bird inhabited our country, it was never discovered whither it betook itself on its annual disappearances from its favourite breeding resorts; whether to Spain or Africa, or only to some other part of Great Britain. The fact that it punctually reappeared in many of its haunts as early as January each year, shows that it did not go very far afield. Stevenson does not concern himself much about the bird as an individual—its manners and customs; his account is rather like a history of a people, or race, which is apt to be a chronology and record of principal events - stratagems and spoils, manoeuvres, massacres, pursuit of fugitives, etc., etc. His account opens solemnly: ‘With almost kindred feelings to those with which one contemplates in the human race, the extinction of some great historic name, the naturalist, at least, regards the extermination amongst us of this noble indigenous species.’ That so noble a figure was ever indigenous, a member of an avi-fauna now composed of comparatively mean forms, reads almost like a tale of fancy. Yet this grand bird was once quite common in all open localities suited to its habits throughout the country—the moors of Haddingtonshire and Berwickshire; Newmarket and Royston heaths; the downs of Berkshire, Wiltshire, Dorsetshire, Hampshire and Sussex. In all these localities, Stevenson states, it had ceased to exist before the last of the race of British Bustards fell victims to the advancement of agriculture in its last haunt in Norfolk and Suffolk. It was, in other words, deliberately extirpated. In Wiltshire it ceased to exist about 1820; in Yorkshire about 1825, when a pair were killed at Malton, and a female bird was taken alive and tethered on a lawn as a curiosity; in the open parts of Norfolk and Suffolk it lingered on to 1832 and 1833. But for many years before that date it had been pursued in that ruthless manner which seems to indicate on the part of the persecutors a fixed relentless determination to wipe the species out—the spirit of the gamekeeper with regard to Hawks, Owls, the Magpie, Jay, and other species that still exist to give variety and lustre to our wild bird life, and redeem it from that oppressive sameness which is fast becoming its most prominent characteristic. As long back as 1812 one Turner of Wrotham conceived an ingenious plan for the quick dispatch of Bustards, which won him the title of otidicide, and some substantial benefits.

Of the landowners in the district where the last Bustards continued to breed, Stevenson says: ‘Not a thought of the extermination of the species seems to have passed through their minds. Either they were entirely indifferent about the matter, or else they believed that since, as long as they could remember, there had always been Bustards on their brecks, therefore, Bustards there would always be.’

In his work (1837) Selby expressed the hope that no endeavour would be spared to prevent the total extinction of so noble a native bird. Alas, the forces of Philistinism and brutality were too strong in that day to admit any such hope. As they are ten times more powerful now, unless the people of England will awake to the fact all that is yet left of their finest wild bird life will go the way of the Great Bustard.

From time to time Bustards have straggled to England since their extermination as a breeding species. Thus, many were seen and shot in 1870 and in 1879-80, and single birds have been shot in Hampshire and Wilts in more recent years. A definite attempt to re-establish the Bustard has also, been made, but without the success which has attended the re-introduction of the capercaillie. At the beginning of the present century Lord Walsingham, one of the few naturalists who, instead of spending time and means in seeking to exterminate rare species, endeavoured to enrich our avi-fauna by adding to the list—made an effort at great expense to re-introduce the Great Bustard. He imported seventeen from Spain, and these were placed on Lord Iveagh’s estate at Elvedon, Norfolk, where they had the freedom of some 800 acres of suitable country which might, it was hoped, become the nursery of a new British race. But in the following year, when they began to go beyond the boundaries of their Elvedon sanctuary, the fate which might have been anticipated befell them, in spite of attempts made to ensure their safety at the hands of neighbouring landowners. They appear to have spread themselves over the country, and it was not long before records of the shooting of them showed that the experiment was doomed. In June 1901 a gamekeeper was fine for killing two of these the most splendid of gamebirds, and their skins were given to the Ipswich Museum. Doubtless they were two of the Elvedon birds. By the end of the following year only two of the seventeen remained, and these reared no young and disappeared.

All that remains of the Great Bustard in England is the mention of its name in the lists of birds scheduled for special protection in some half-dozen counties. It is hardly likely that there will ever again be English Bustards to protect.

‘The ‘droves’ which roamed over the Yorkshire wolds, Salisbury Plain, and similar uncultivated areas were often immense, but the bird was too big and edible to survive. Spread of cultivation, increase of population, and perhaps more than either, improvement of sporting guns, swept them away.— T. A. Coward, Birds of the British Isles.

‘It passed away unrecorded, from Berkshire, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, the wolds of Lincolnshire, and the downs of Sussex, while the first ten years of this century saw the extinction of the birds indigenous to Salisbury Plain. On the Eastern Wolds of Yorkshire the survivor of former droves was trapped in 1832-33; and in Norfolk and Suffolk the last fertile eggs were taken about 1838, though a few birds lingered to a somewhat later date. The Bustard is now only an irregular wanderer to Great Britain.’— Saunders’s Manual.

‘The last examples of the native race were probably two killed at Swaffham, in Norfolk, a district in which for some years previously a few hen-birds of the species, the remnant of a plentiful stock, had maintained their existence. In Suffolk, where the neighbourhood of Icklingham formed its chief haunt, an end came to the race in 1832; on the wolds of Yorkshire about 1826, or perhaps a little later; and on those of Lincolnshire about the same time. Of Wiltshire, Montagu, writing in 1813, says that none had been seen in their favourite haunts on Salisbury Plain for the last two or three years. From other British counties, as Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, and Berkshire, it disappeared without note being taken of the event.’— Newton’s Dictionary of Birds.”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend