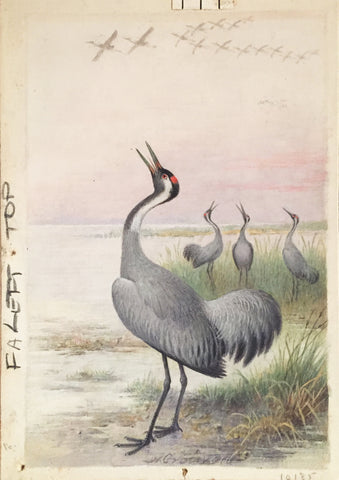

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Grus Cinerea (Crane)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Grus Cinerea (Crane)”

Prepared for Plate II W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper

Signed ‘H. Gronvold’. Inscribed with notes to the publisher.

1922-1923

Paper size: 7 1/4 x 5 1/8 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“The Crane remained with us down to the time when people wrote about British Birds—the times of Turner, Willughby, and others. Turner (1544) says, ‘Cranes breed in England in marshy places, I myself have very often seen their pipers,’ pipers being the name given to the young birds. It was once common, and continued to resort to our shores in considerable numbers down to nearly the end of the seventeenth century. It was abundant in Ireland, we know, in the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. When it ceased to breed is not certain. In the sixteenth century it was, with other large game birds—Heron, Bittern, Spoonbill, Bustard, etc.,—protected by Act of Parliament. This was a wise law, that gave protection to egg as well as bird, but in the case of this species it was of no avail. Sir Thomas Browne, in his Account of the Birds found in Norfolk, tells us that ‘Cranes are often found here in hard winters, especially about the champain and fieldy parts. ... It seems they have been more plentiful, for in a bill of fare when the Mayor entertained the Duke of Norfolk I meet with Cranes in a dish.’ This feast is supposed to be one which was given in June 1663.

Willughby, in 1676, says : ‘They come to us often in England, and in the ten counties, in Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire, there are great flocks of them.’ As to whether or no they bred at that time he says, ‘I cannot certainly determine, either from my own knowledge or from the relation of any credible person.’

At the present day the Crane is a rare visitor—a lost wanderer from happier realms. The resonant, far-sounding cry of this noble bird—one of the most fascinating sounds of wild nature, especially when several individuals, as their custom is, unite their voices in a chorus—will probably never be heard again in England, except from rare stragglers or from captives in an enclosure. Occasional visitations we have; there was a great and notable one in the spring of 1869; but the birds are always shot on appearance. Mr. H. E. Forrest records in his Fauna of Shropshire that one was shot on the Herefordshire border in 1859 by a farmer who, finding it described in the books as a ‘common’ Crane, gave the body to his waggoner, who cooked and ate it. A writer in British Birds (Vol. II.) states that a female bird shot in Anglesey by a gamekeeper in May 1908, showed no sign of having been in captivity and was stuffed and placed in Chester Museum where ‘it forms an extremely interesting addition to the local collection.’ The shooting of a rare visitor or of an escaped bird from a private aviary, represents the only way in which additions are made to the British avi-fauna to-day. With the Crane’s figure we are perhaps more familiar than with that of any other large species, and will be so as long as we continue to import decorative hangings, screens and pictures by the million from Japan. To that artistic people the Crane is pre-eminent among birds for its beauty and stately grace as is the chrysanthemum among flowers. ‘An Act passed in 1534 fixed a close time from May 31st to August 1st, during which wild fowl might be taken by certain methods, and by certain persons, under a penalty of a year’s imprisonment and a fine of 4d. A heavier fine was imposed on stealers of eggs, amounting to as much as 8d. for the eggs of Shoveller Duck, Heron, or Bittern, and 2od. for that of Bustard or Crane.

Mr. T. Southwell, writing in Archceologia,Vo\. XXXVI., quotes from the sixteenth-century list of presents sent to William More of Loseley by Mr. Bolan out of Marshland in Norfolk, nine cranes, nine swans, and six bitterns, with a large number of other wild fowl.”

‘Notwithstanding the protection afforded it by sundry Acts of Parliament it has long since ceased from breeding in this country. Sir. T. Browne (ob. 1682) speaks of it as being found in the open parts of Norfolk in winter. In Ray’s time it was only known as occurring in the same season in large flocks in the fens of Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire; and though mention is made of Cranes’ eggs and young in the fen-laws passed by a court held at Revesby in 1780, this was most likely but the formal repetition of an older edict, for in 1768 Pennant wrote that after the strictest inquiry he found the inhabitants of those counties to be wholly unacquainted with the bird, and hence concluded that it had forsaken our island. The Crane, however, no doubt then appeared in Britain, as it does now, at uncertain intervals and in unwonted places, showing that the examples occurring here (which usually meet with the hostile reception commonly accorded to strange visitors) have strayed from the migrating band whose movements have been remarked from almost the earliest ages.’ —Newton, Dictionary of Birds.”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend