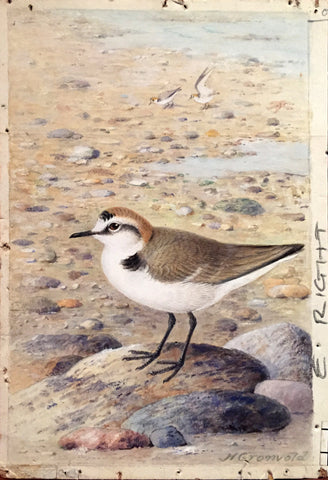

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Gialitis Cantiana (Kentish Plover)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Gialitis Cantiana (Kentish Plover)”

Prepared for Plate XXII W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper or card

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.r.

1922-1923

Paper size: 7 7/8 x 5 5/8 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“Both names, common and scientific, fit the bird, first described in 1781 as an inhabitant of the Kentish

coast, and surviving now only on the flats of Dungeness, where men are engaged by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds to save the few remaining birds and their eggs from the prowling scoundrels employed by the collectors.

The Kentish Plover, if not so strikingly coloured as its near relative the Ringed Dotterel or Plover and many others in this pretty group, is a peculiarly neat and graceful little bird, with a subdued colouring which harmonises with the level world of its desolate habitat. To the ordinary observer it appears as a smaller and paler Ring Plover, with less distinct markings but with the same dainty attractive ways. It is a summer visitor and spends no more than the actual breeding-time with us. That it will continue to return for long is doubtful, unless a law prohibiting the possession of rare birds and their eggs is obtained. A Sandwich ornithologist was the first to call attention to the species, by sending specimens to Latham, from which it was figured in Lewin’s Birds of Great Britain and described in Latham’s Supplement to his Index Ornithologicus. According to Yarrell it was in his time still found in the Sandwich neighbourhood and also at Pegwell Bay. It was seen too in various other places on the south and east coasts, but is not known to have bred in any other counties than Kent and Sussex.

A few years later it was Yarrell who first put the collectors on to the too well-known breeding-ground at Dungeness. Particulars of this were supplied to him by Plomley, who, it is said, ‘afterwards deeply lamented the part he played in the extermination of the species.’ This lament he set down in some MS. notes quoted by Dr. N. F. Ticehurst, whose History of the Birds of Kent tells the story of this essentially Kentish species. “ Of all birds,” Plomley avows, ‘these are my especial favourites . . . and I shall always regret having made known the locality in this county where they abounded and where (until my notice of them in Yarrell’s book) they lived, enjoyed, and brought forth their young, unnoticed, undisturbed and unseen.’ Plomley, however, over-estimated the part he played in the matter. The birds were already known to have their chief breeding-ground on the coast near the Kent and Sussex border, for Yarrell himself relates that dogs were trained to hunt for their nests and eggs; and the collector was as keen on the scent as the dogs, and would certainly have tracked the birds down as industriously. Four years after the giving away of the Dungeness secret to the ornithological public of that day, the birds were already fast disappearing. And the hunt went on until these little birds, so pretty in their appearance and ways as they lightly tripped over the shingly beech, so harmless and so innocently tame in the presence of their arch-enemy man, were on the point of extermination in this country.

Not only were the eggs searched for with avidity, but the birds themselves were ruthlessly shot during the breeding season, and such young as were hatched were destroyed with the adult birds by another onslaught in September before they could get away from England. The wonder is that any survived. I will here again quote Dr. Ticehurst:

‘The eggs, we know, were constantly taken both by collectors from a distance and by the local people to supply the ever-ready market, but the chief cause to my mind of the almost successful extermination of the species was the shooting of the old birds during the breeding season, which went on more or less every year until the appointment of an authorised Watcher. As recently as 1902 I received information of twenty-one being killed, of which at least six pairs were old birds shot in the breeding season.’

This, be it noted, was twenty years after the passing of a law prohibiting the killing of all birds at that season and scheduling the Plovers for the fullest protection the Act could give. In ornithological circles the fact of the slaughter was of course known; we readily understand why nothing was said or done.

‘Another factor that has been detrimental to their increase has been the shooting in August. At this time young and old are to be found in flocks on the sands, and being very tame, large numbers not only fall to the gun of the pot-hunter, but I have it on good authority that professional collectors were in the habit of firing into the flocks and picking up the adult birds only, leaving the immature birds dead and dying on the sands.’

At what seemed the last moment, or as a forlorn hope, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds made a desperate effort to save the remnant of the British Kentish Plovers, and they still continue that effort. By untiring vigilance, and in spite of shameless attempts to overcome this by bribe and stratagem, the feeble little company has even increased of late years. That it will go on increasing is an anxious hope, but far from certainty as long as the private collector can laugh at a law which leaves him outside its futile enactments.

No more damning evidence of that futility can be required than the shameful story of Kent’s little Plover.

‘The Kentish Plover is one of the most local of British birds, and has only been obtained very sparingly on the south and east coasts of England, as far north as Flamborough Head in Yorkshire and as far west as Cornwall. Its only breeding places in the country appear to be on the coasts of Kent and Sussex; but even there it is a rare bird, and is fast disappearing before the inroads of collectors.’— Seebohm’s British Birds.

‘Protection was just in time to save the Kentish Plover; it nearly came too late.’— Coward’s Birds of the British Isles.”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend