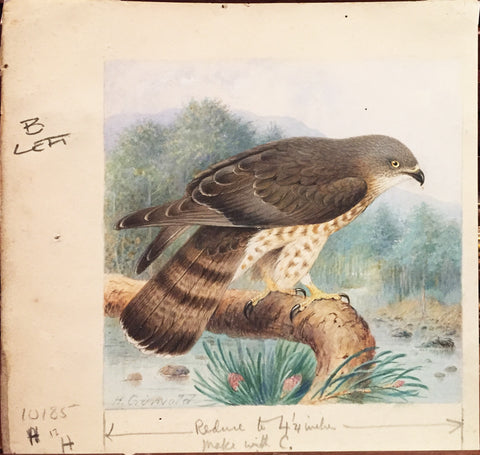

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Pernis Apivorus (Honey Buzzard)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Pernis Apivorus (Honey Buzzard)”

Prepared for Plate XVII W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.l.

1922-1923

Paper size: 7 1/4 x 7 1/2 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“In the time of the earliest of our ornithologists, and we know not for how many centuries before his day,

the Honey Buzzard was a common British bird. It was one of our finest Hawks, equal in size to the (so-called) Common Buzzard, beautiful in appearance, harmless and interesting in its habits. It did not, like many other Hawks, attack game, but was content with such small deer as wild bees and wasps and their grubs, grasshoppers, small reptiles, and the like. None of these things availed to save it. It was a Hawk: that was enough for the gamekeeper. It was a large Hawk; therefore it must be the more mischievous. And as it became more and more uncommon, so its skin and eggs became the more desirable in the eyes of the collectors. In the nineties of last century the bird was finally exterminated as a British species.

The Honey Buzzard, a summer migrant to this country, used to breed in all extensive woods. Willughby wrote: ‘It hath not yet, that we know of, been described by any writer, though it be frequent enough with us ;’ and in the middle of last century Knox wrote that it was commoner in Sussex than either the Kite or the common Buzzard, words which meant more in his day than they do in ours. The description of the Selborne bird and nest in White’s letters to Pennant is well known: how in 1780 a pair of Honey Buzzards built a large nest, composed of twigs and lined with dead beechen leaves, upon a tall slender beech tree near the middle of the Hanger; how a bold boy climbed the tree ‘though standing in so steep and dizzy a situation,’ and brought down the one egg; and how the bird was then shot and found to answer exactly Mr. Ray’s description of the species, while in its craw were some limbs of frogs and many grey snails without shells.

Montagu mentions that the Honey Buzzard was very rare in his time, and cites a specimen killed at Highclere, on the Hants and Berks border; and Seebohm wrote in 1885: ‘It is a great pity that such an extremely handsome and entirely harmless bird should be on the verge of extinction in our country. In addition to the persecution of game-keepers, who have not yet learned to distinguish between useful and harmful birds of prey, it is much sought after by collectors, both for its skin and its remarkably handsome eggs. In spite, however, of all its enemies, it still yearly breeds in the New Forest and some other parts of England and Scotland.’

From all its habitats, except the New Forest, it had probably disappeared before this passage was written. The usual rush was made for it by the ornithologists who hold that when a species is on its last legs (or wings) is the time to fight for the glory of securing the last British-killed specimen of the bird, the last British-taken egg. The disgraceful end soon came.

Mr. Meade-Waldo, writing in the Victoria History of Hampshire , says that the principal war of extermination was between i860 and 1870, but that in 1880 an attempt was made to give protection to this and other interesting inhabitants of the Forest. But, he adds, ‘for this particular bird it seems to have been too late, and I do not know a single authentic case of its having bred since that date.’ It was indeed more than twenty years too late. About 1860, as Howard Saunders tells us, ‘it was known that several pairs annually resorted to the New Forest. Five pounds soon became the standard price which collectors of ‘ British 9 specimens were willing to pay for a couple of well-marked eggs; and to these inducements were added such extravagant sums as nearly £40 for the pair of old birds. By about 1870 the birds which had not been killed were driven away; and if any have since returned the persons acquainted with the fact have exercised a becoming reticence on the subject.’ Mr. Meade- Waldo says that a female bird was shot in Brockenhurst Park in 1887, and that Mr. Hart answered for a case of the bird nesting in the Forest in 1895. He adds that in the following year, 1896, he himself noticed a bird frequenting one part of the Forest which invariably took the same flight—the only instance, he says, in which he had seen a Honey Buzzard whose actions suggested that it might have a nest, though he had watched year after year and met pretty frequently with individual birds. That one instance is now a quarter of a century old. We may conclude that the Honey Buzzard is a lost British bird. Nests recorded in the Zoologist , at Hereford in 1895 and on the banks of the Derwent (Durham) in 1899, can only be regarded as accidental.

‘The Honey Buzzard was formerly a regular summer visitant to this country, breeding in most of the counties of England and Wales where the woods were large enough to afford it a secure retreat. In Scotland and Ireland the information we have is very meagre; but it appears to have formerly bred in both countries, where it has now, as well as in England, become a rare summer visitor. It is also occasionally seen on the autumn migration. It is a great pity that such an extremely handsome and entirely harmless bird should be on the verge of extermination in our country. In addition to the persecutions of the game- keepers, who have not yet learnt to distinguish between useful and harmful birds of prey, it is much sought after by collectors, both for its skin and for its remarkably handsome eggs. In spite, however, of all its enemies it still yearly breeds in the New Forest and some other parts of England and Scotland.’—Seebohm’s British Birds.

‘The Honey Buzzard is now mainly known in our islands as a rare spring and autumn visitor on passage, but has a perfect right to rank as a scarce summer visitor, since within recent years it has nested in many parts of England and southern Scotland. At one time it was undoubtedly a regular breeder, and until about 1870 nested annually in the New Forest.’— Coward’s Birds of the British Isles.”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend