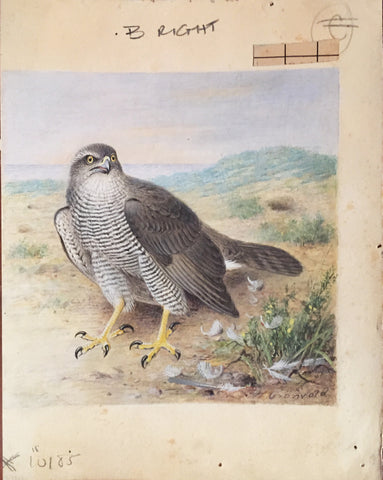

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Astur Palumbarius (Goshawk)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Astur Palumbarius (Goshawk)”

Prepared for Plate IX W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on paper

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.r.

1922-1923

Paper size: 8 x 6 1/2 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“Though probably never abundant, this bird was nevertheless an indigenous species in this country and was the noblest of our Hawks properly so-called, as distinct from the Falcons. In form and colour it resembles the Sparrowhawk, but in size is considerably larger, and it flew at bigger game. In old laws the taking of its eggs was prohibited in company with those of the Peregrine Falcon, so that in certain districts it was perhaps fairly common, and we know that it bred in Scotland down to the first half of the nineteenth century. At the time when falconry was the sport of the landed classes it was known also as the ‘Falcon Gentil,’ and was much valued for pursuing such quarry as Mallard, Wild Goose, hare, and rabbit. Goshawks from the north of Ireland were the best in the world, according to Sir James Ware, who lived in the first half of the seventeenth century. The Tyrone Goshawks are also cited in Richard Blome’s The Gentleman’s Recreation (1686), as, with those from Muscovy and Norway, the best for sport.

Coming to later times, Dr. James Hill in his History of Animals (1752) speaks of the Goshawk nesting in Northumberland, and Colonel Thornton (1804) found it breeding in the forests of Glenmore and Rothiemurchus, where Selby also records it thirty years later, remarking that it had then disappeared from the country south of the Tweed, but still bred in the forest of Rothiemurchus, on the banks of the Dee, and on rocks in the Orkney Islands. There is no evidence later than Thornton’s of the use of the bird in falconry. Its extinction was due to the destruction of forests and the growing passion for game preserving. On one Highland estate, as Knox relates in his Game Birds and Wild Fowl, the game-keepers in the course of three years, 1837-40, destroyed 63 Goshawks and 275 Kites. In 1847 St. John speaks of the Goshawk as “ now nearly extinct in this country, whereas a few years ago it bred regularly; ” and Robert Gray in his Birds of West Scotland (1871) writes: ‘Within a comparatively recent period I have known the Goshawk breed in Kirkcudbrightshire;’ and he adds that a pair of Ravens were driven from their nest by Goshawks, who appropriated it to their own use.

The deadly persecution of birds of prey which, beginning in the 18th century, has continued down to our own time, and has led to the disappearance of all large birds but the few now left to us, sealed the fate of this the largest of our Hawks. It lingered a little longer as a regular breeder after St. John wrote, and then vanished, re-appearing occasionally, but only to be shot. I was one day conversing with a great landowner and nobleman in his park, about birds, when he invited me to go to his library in order that he might show me the birds he most admired. I followed him, though not expecting to see the bird which most won his admiration: and was shown a drawing of a Goshawk. ‘This,’ I said, ‘is a picture of a Goshawk, but where is the bird ?’ He replied that it no longer existed in Britain. ‘Is not that,’ I returned, ‘because the men who own the land and the woods of Britain have exterminated it ?’ He answered: ‘I suppose so;’ and added, ‘You see we could not very well have so many pheasants as we require for sport if we allowed birds like the Goshawk to live.’

This is the spirit in which landowners and their keepers have for many years been engaged in trying to exterminate first the Goshawk and after it the Sparrowhawk, but in the case of the latter they have not quite succeeded yet, so that we still have one representative of a magnificent type of the rapacious bird.

Even in the present century the Goshawk has made attempts to breed in this country. It has been urged that the birds in these cases had escaped from captivity, but no evidence has been found for such a supposition. The fact of a nest having been found in Yorkshire three-quarters of a century after the last record came out by a curious chance. In May 1878 a passing reference to the extinction of the Goshawk as a British species caught the eye of a resident in Yorkshire, and particulars of an instance known of a breeding bird were made public by Mr. T. Southwell in the Zoologist in 1899. The nest, containing four eggs, was found in a wood in Westerdale in Cleveland, placed on the branch of a spruce fir about twenty feet from the ground. ‘It was very large and flat, and the bird was wild and difficult to get a shot at. Eventually she was enticed by an imitation of her cry.’ She was shot and the eggs taken.

Then comes the final story. In 1903 a pair of Goshawks built a nest close to Cheltenham, a singular and curiously interesting event in the ornithological records of Gloucestershire. Such an occurrence in a remote forest in the wilds of Inverness would still have been of great interest; that these wild and fierce Falcons, known to living men as British birds only through the testimony of museums, should return and build in the middle of populous England, close to such a place of all others as Cheltenham, might well confound the naturalist. The eggs were taken and identified at the Natural History Museum. The next year the birds returned and nested at the same spot. This time both were shot by the owner of the land and the remains sent to a local bird-stuffer for what is ironically termed preservation. ‘It was a dastardly act,’ wrote Mr. Charles Witchell, who relates the facts. ‘The birds were not alleged to have done any damage, and if they had there would have been persons willing to pay for it rather than that two such interesting and rare birds should have been destroyed at their breeding time.’

‘A dastardly act’ we all echo, and this dastardly act closes the record of the British Goshawk.”

‘The Goshawk was probably never a common bird in the British Islands; and of late years, since the forests have nearly all been cut down and game-preserving has become so universal, this noble bird of prey has become only an accidental visitor. It is only within the last half-century that it has ceased to breed in Scotland. The Goshawk is not strictly a migratory bird, otherwise it would probably appear much more commonly in this country. Many birds of prey zealously guard their hunting-grounds from trespassers of their own species, and drive away their own young to seek new breeding-grounds. The Goshawk is no exception; and occasionally one of the young birds finds its way to our shores. They usually arrive on the east coast, and soon fall a prey to the gamekeeper or the birdstuffer.’—Seebohm’s British Birds.

‘There can be little doubt that the Goshawk, nowadays very rare in Britain, was once common in England, and even towards the end of the last century Thornton obtained a nestling in Scotland, while Irish Goshawks were of old highly celebrated. Being strictly a woodland bird, its disappearance may be safely connected with the disappearance of our ancient forests, though its destructiveness to poultry and pigeons has doubtless contributed to its present scarcity.’— Newton’s Dictionary of Birds (1896).”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend