Elizabeth Washington Gamble Wirt as “Mrs. E. W. Wirt, of Virginia” (1784-1857), Flora's Dictionary

Elizabeth Washington Gamble Wirt as “Mrs. E. W. Wirt, of Virginia”

Flora's Dictionary

Baltimore: Fielding Lucas Junr., [1837]

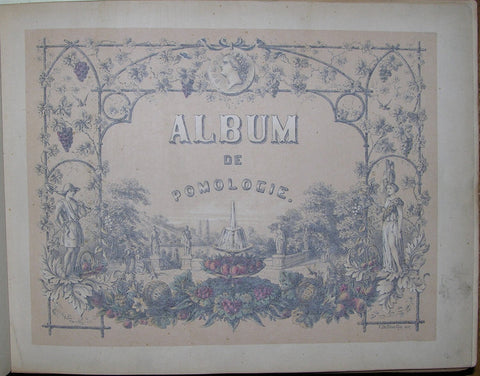

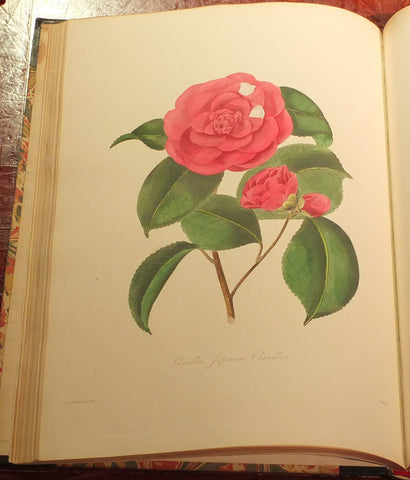

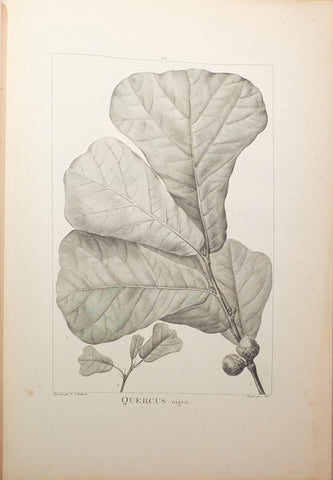

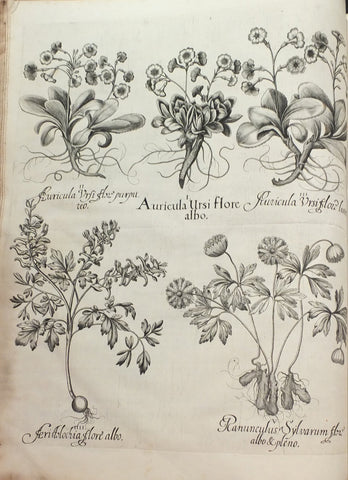

4to., (10 3/8 x 8 inches). Pictorial lithographed title page and dedication page, both with original hand color. 56 lithographed plates with original hand color (one plate torn affecting image, somewhat browned, occasional offsetting). Original publisher’s maroon morocco gilt, the spine in five compartments separated by four raised bands, gilt-lettered in one and decorated in the rest (hinge starting, extremities a bit worn, one or two pale stains).

Second edition thus, first published anonymously as Flora’s Dictionary by “a Lady” in 1829. “The arrangements of the flowers are beautifully balanced and the coloring is brilliant” (Bennett, p. 115). The main section of text of Flora’s Dictionary is made up of about 230 entries arranged alphabetically from Acacia Rose (friendship) to Zinnia (absence). Each entry includes a brief definition (Laburnum: pensive beauty; Ranunculus: I am dazzled by your charms; etc.), followed by a selection of appropriate verses, from both the classics and contemporary authors.

“While it is pleasant to think that the introduction of the language of flowers to America was accomplished by a man [Rafinesque] born in Turkey (as the language itself was said to be) who was also a citizen of France, the country of its introduction to society, it fell to a “Lady” of Virginia to really popularize the concept for American consumers. Elizabeth Gamble Wirt (1784-1857) was the second wife of William Wirt, attorney general of the United States and author of The Letters of the British Spy and other popular works. Her Flora’s Dictionary (1829), published under the pseudonym “A Lady,” was a phenomenal success. According to her preface, she had put together her language of flower list from several ‘books and manuscripts’ over the past few years, and she only allowed it to be published because she was not able to supply all the manuscript copies people asked for and because someone in Boston had, ‘last year,’ put her material in print. This Boston edition of Flora’s Dictionary (if indeed it was called that) is unknown to me, and she remarks concerning it that ‘few copies were struck, with great neatness and beauty of type and paper.’ Her purpose in mentioning this Boston printing is, she says, to let those who have copies to know whose work it is and also understand that she had no ‘original purpose of publishing’…

“The illustrations in the language of flower books have only a small role in the history of botanical art, for they emphasize sentiment and romance over accuracy. However, they are often very attractive and are particularly evocative of the period’s perspectives on nature. In fact, there is a tendency today, in America certainly, to use flower illustrations as a cultural shorthand to represent the previous century, at least the years after 1840. Stylized roses – fat cabbage roses with a few ferns or drooping lily of the valley – are typically symbolic of the Victorian period. Such common images, while accurate, are not the whole story in sentimental flower book art, which went through a number of technical changes and which was sometimes associated with well-known artists” (Beverly Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History). Rinderknecht 48537. Sabin 104868. Bennett, p.115. McGrath, p.36; Reese Stamped with a National Character 52.

We Also Recommend