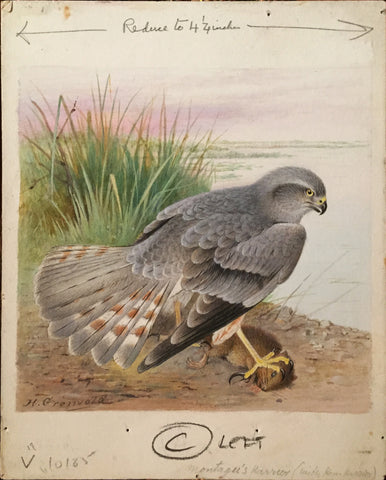

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940), Circus Cineraceus (Montagu’s Harrier)

Henrik Grönvold (Danish, 1858 –1940)

“Circus Cineraceus (Montagu’s Harrier)”

Prepared for Plate XVI W.H. Hudson and L. Gardiner, Rare, Vanishing and Lost British Birds (1923)

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache, some with touches of gum Arabic on card

Signed ‘H Gronvold’ l.l.

1922-1923

Paper size: 8 1/2 x 6 7/8 in.

Provenance: Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 17 March 1999, lot 149, private collector.

“As this Harrier, known as the Blue Hawk, was not recognised as a separate species from the somewhat larger Hen Harrier until distinguished by Colonel Montagu, it is impossible to arrive at the status of the bird in Great Britain before the nineteenth century. There is, however, no doubt that it was far more common at the opening of the century than at its close. In all probability the original British race ceased to exist and its place has been taken in later years by fresh migrants, the species being at all times only a summer resident. Its position in England is said to have slightly improved in the last decade. According to Mr. J. H. Gurney it nests fairly regularly on the Norfolk Broads and fens and hatched out young in 1918, and again in 1922. In Hampshire, where the New Forest was one of the old homes of the species, its history is no more creditable than that of the Honey Buzzard. Mr. Corbin, writing in the Zoologist (1875) narrates that on one day he observed a bird near the Dorset border and ‘for several consecutive days its presence was to me a source of pleasure.’ Soon afterwards a Montagu’s Harrier was trapped and brought to him. ‘Since then I have seen several others, especially males, at the bird-stuffers in neighbouring towns, and during the spring of 1874 I was highly gratified at seeing two, if not three, pairs in the New Forest, where the species undoubtedly breeds most seasons. A gamekeeper trapped two pairs, and I did not see the others afterwards.’

Messrs. Kelsall and Munn state that it is now (1905) ‘by far the most common Harrier in this county, and we believe there are two districts, besides the New Forest, where it appears annually, and attempts, with more or less success, to rear its young.’ It also attempts “ with more or less success ” to nest in several other counties. I quote the following list from the Additions to our knowledge of British Birds since 1899, published in British Birds , 1908 and 1909:

1893. Two pairs bred in the Cambs fens. One nest taken. Eggs laid in East Sussex, bird and nest destroyed.

1898. Nest with young found in S.E. Hampshire, “ and this haunt still visited by the birds.”

1900. Pair nested at Bala, bird shot.

1903. Eggs again laid in E. Sussex, birds and nest destroyed. Nest with two eggs found in Yorks, female caught.

1905. Bird shot in Northumberland, apparently while incubating. Male shot in Notts, probably had a mate nesting.

1906. Adult female shot in Norfolk.

1907. Pair nested in Surrey, failed to hatch out. Male and female, Norfolk, both shot.

An editorial note is appended to the Norfolk records: ‘It may be pointed out (since it is not

generally recognised) that as long as keepers know that they can dispose of such birds, the more inclined they will be to destroy them.’ Until this fairly obvious fact is recognised, and until the private collector ceases to be countenanced by the ornithologists of this country and by the law of this country, the chances for these and other rare birds are small.

‘In this country, though in no parts numerous, it is generally dispersed.’— Morris’s British Birds.

‘Though formerly a resident in Great Britain, Montagu’s Harrier is now only an accidental visitor, occasionally breeding where it is left unmolested. It is still rarer in Scotland.’— Seebohm’s British Birds.

‘A hundred years ago this species was very much more common than it is now, although comparatively recent instances of its breeding are known in Devonshire, Somerset, Dorset, and Hants. Its principal haunts at the present day appear to be the heaths of Norfolk. Possibly the bringing of common lands into cultivation may have had some influence in reducing the numbers of this Harrier; but there can be no doubt that the persecution of gamekeepers has had infinitely more. If we are to retain this elegant and pretty bird in our fauna, measures will have speedily to be taken, for all the available evidence at the present day goes to show that this Harrier is upon the very verge of extinction. The old stock of birds that has been in the habit of migrating to Britain is nearly exhausted, and if the few remaining pairs are not shown some consideration, the species must cease to exist as a British one.’—C. Dixon, Lost and Vanishing Birds (1897).

‘Nests annually East Anglia, fairly regularly in Cambs, Hants, Dorset, and Devon, and occasionally elsewhere, as in Cornwall, Isle of Wight, Sussex, Surrey, Yorks, and Merioneth, and possibly Somerset, Notts, and Northumberland. Rare vagrant in Scotland and Ireland.’— Witherby’s Handbook, II. 154 (1921).”

HENRIK GRÖNVOLD (DANISH, 1858 –1940)

Henrik Grönvold studied drawing in Copenhagen and worked first as a draughtsman of the Royal Danish Army’s artillery and an illustrator at the Biological Research Station of Copenhagen. In 1892, Grönvold left Denmark for London, employed at the Natural History Museum preparing anatomical specimens. There he became a skilled taxidermist and established a reputation as an artist. He was employed at the Museum until 1895 when he accompanied William Ogilvie-Grant on an expedition to the Salvage Islands. After this expedition, Grönvold worked at the Museum in an unofficial capacity as an artist for decades and only left London to attend an ornithological congress in Berlin.

Grönvold’s illustrations mainly appeared in scientific periodicals such as the Proceedings and Transactions of the Zoological Society, The Ibis, and the Avicultural Magazine. In these publications, he drew plates for William Ogilvie-Grant, George Albert Boulenger, and Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas, among others. Grönvold also completed numerous plates for Walter Rothschild, many of which appeared in Rothschild’s journal Novitates Zoologicae. Grönvold mostly illustrated birds and eggs, rare and newly discovered species from many parts of the world, and mostly worked in lithographs.

Among the books, Grönvold illustrated is George Shelley’s Birds of Africa, which contained 57 plates, many of which had not been illustrated before. He illustrated W. L. Buller’s books on the birds of New Zealand, Brabourne’s Birds of South America, Henry Eliot Howard’s The British Warblers (1907–14), Charles William Beebe’s A Monograph of the Pheasants (1918–22), and Herbert Christopher Robinson’s The Birds of the Malay Peninsula (1929–76). He completed 600 hand-colored plates for twelve volumes of The Birds of Australia (1910–27) by Gregory Macalister Mathews. Grönvold subsequently provided numerous illustrations for Mathews’ The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1928) and A Supplement to The Birds of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands … (1936).

ORIGINAL WATERCOLORS FOR RARE, VANISHING

AND LOST BRITISH BIRDS

by Henrik Grönvold for William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841-1922) was a naturalist, author, and staunch advocate for avian preservation and conservancy. Hudson’s lifelong commitment to protecting the environment stemmed from his youth in Argentina, where he marveled at the beauty of nature, spending endless hours watching the drama of forest and field unfold before him. This idyllic upbringing was beautifully penned in the artist’s work Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which remains a cult favorite amongst many novelists, including Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that Hudson’s book was a must-read for any young writer.

Hudson gravitated to studying birds, which guided his life’s work as an ornithologist and author of numerous tomes on the subject. When he settled in England in 1874, he joined the numerous societies for naturalists of the period and became a founding member of the Royal Society to protect birds.

In 1894, W.H. Hudson produced a leaflet titled Lost British Birds produced for Society for the Protection of Birds. Its purpose was to shed light on thirteen “lost” birds which he defined as those “which no longer breed in this country and visit our shores only as rare stragglers, or, bi-annually, in their migrations to and from their breeding areas on the continent Europe,” to concretely show the effect of industrialism, game hunting, and fashion on the sustainability of certain bird species. This pamphlet was illustrated with 15 rudimentary black and white line drawings by A.D. McCormick. Almost immediately after producing his brochure, Hudson began to collect notes for a future publication that would elaborate upon and update facts on endangered and extinct bird species.

Hudson spent the nineteen-teens and early twenties preparing his next publication. When his notes were organized, and he tapped the celebrated ornithological painter Henrik Grönvold (1858-1940) to produce a sophisticated full-color composition for each bird he intended to discuss at length. However, Hudson suddenly died in 1922 before the publication could come to fruition. Hudson’s colleague, Linda Gardiner, pushed the project forward to see it through in 1923.

Please feel free to contact us with questions by phone at 215.735.8811,

or by email at loricohen@aradergalleries.

We Also Recommend